Even before BBC2 came on the air in 1964 there had been a debate concerning who should own a fourth television channel. ITV wanted it because (as they pointed out) the BBC with the advent of BBC2 had two channels whereas ITV had only the one, though by 1979 ITV’s viewing figures were exceeding the combined BBC1 and 2 figure so this argument started to sound weak (even if many TV sets had their fourth button marked ‘ITV2’ since it seemed logical). Back in 1964 the Conservative Party promised ITV that it would get the fourth channel if they won that year’s election – they didn’t win, so the issue was postponed as other factors took precedence. Work was progressing slowly, though by 1979 it seems that progress towards a fourth channel was at last starting to make some headway.

The 1979 General Election was predicted to be the crucial factor as to what the fourth channel would be like. If the Labour Government was returned to power again, the fourth channel would be run by an organisation known as the OBA (Open Broadcasting Authority). This was a popular choice (as opinion polls showed) since it would be completely different from the established channels’ programming, being community-based and non-profit making. However it was predicted that it would only have (roughly) a 2% audience share, and there were unanswered questions in relation to funding such an enterprise.

That did not happen (of course); the Conservative Party came to power, led by Margaret Thatcher – they were predicted to give the new channel to ITV in order to give them their ITV2. Another alternative discussed at the time was to create an entirely separate new commercial channel (the approach favoured by the advertising agencies – they hoped that the aggressive competition between two openly competing commercial channels that would be the result would drive down advertising rates); but the end result was surprisingly different from those proposals mentioned even if it featured common elements from all three approaches.

Although initially regulated by the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) with financial cross-subsidy from the ITV franchises, Channel 4 was a broadcaster designed to be independent from ITV, but due to a perceived high risk of financial failure such measures were necessary along with ITV franchises providing some of the programming and being responsible for the channel’s advertising sales, effectively leaving Channel 4 to do what it wanted without having to specifically pander to any of its advertisers. Its remit was and still is essentially similar to BBC2, namely producing specialist programmes for a smaller audience as well as popular programmes, though to begin with Channel 4 was unique in that the majority of programmes were commissioned from small independent production companies.

Although initially regulated by the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) with financial cross-subsidy from the ITV franchises, Channel 4 was a broadcaster designed to be independent from ITV, but due to a perceived high risk of financial failure such measures were necessary along with ITV franchises providing some of the programming and being responsible for the channel’s advertising sales, effectively leaving Channel 4 to do what it wanted without having to specifically pander to any of its advertisers. Its remit was and still is essentially similar to BBC2, namely producing specialist programmes for a smaller audience as well as popular programmes, though to begin with Channel 4 was unique in that the majority of programmes were commissioned from small independent production companies.

Channel 4 launched with a sequence showing clips from various forthcoming programmes, but the very first programme to be shown on Channel 4 when it finally launched on 2 November 1982 was Countdown. Based on a long-running French TV quiz format entitled Des Chiffres et des Lettres (Numbers and Letters), Countdown started life as an regional (Yorkshire) ITV programme entitled Calendar Countdown earlier in 1982 before being commissioned for Channel 4 by controller Sir Jeremy Issacs.

Channel 4 launched with a sequence showing clips from various forthcoming programmes, but the very first programme to be shown on Channel 4 when it finally launched on 2 November 1982 was Countdown. Based on a long-running French TV quiz format entitled Des Chiffres et des Lettres (Numbers and Letters), Countdown started life as an regional (Yorkshire) ITV programme entitled Calendar Countdown earlier in 1982 before being commissioned for Channel 4 by controller Sir Jeremy Issacs.

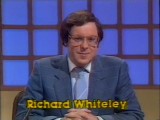

Countdown is a fairly ‘genteel’ quiz based on games that use numbers and letters, and is the only Channel 4 programme apart from Channel 4 News which is still being produced today. The very first presenter to appear on the new channel was none other than Richard Whiteley, who was a familiar face to ITV viewers in the Yorkshire region (Yorkshire TV – now owned by Granada – produces Countdown for Channel 4). Richard became a cult figure nationally as a result of presenting Countdown though he sadly died in June 2005 after an illness.

Countdown is a fairly ‘genteel’ quiz based on games that use numbers and letters, and is the only Channel 4 programme apart from Channel 4 News which is still being produced today. The very first presenter to appear on the new channel was none other than Richard Whiteley, who was a familiar face to ITV viewers in the Yorkshire region (Yorkshire TV – now owned by Granada – produces Countdown for Channel 4). Richard became a cult figure nationally as a result of presenting Countdown though he sadly died in June 2005 after an illness.

One familiar face that appeared on the very first edition of Countdown was that of Ted Moult, who was known nationally to many people as a gardener and also from his appearances on other TV quiz shows. And one person making her TV debut was Carol Vorderman, who was initially just employed as the ‘resident statistician’ and was presented as a graduate from Cambridge University; she of course was later to take greater responsibility for both the letters and numbers games.

One familiar face that appeared on the very first edition of Countdown was that of Ted Moult, who was known nationally to many people as a gardener and also from his appearances on other TV quiz shows. And one person making her TV debut was Carol Vorderman, who was initially just employed as the ‘resident statistician’ and was presented as a graduate from Cambridge University; she of course was later to take greater responsibility for both the letters and numbers games.

The very first Countdown ‘letters game’ produced this selection of consonants and vowels – T, N, E, M, A, R, H, I, B – of which the two contestants were able to think of two seven-letter words ‘raiment’ (an item of clothing) and ‘minaret’ (a thin tower that’s part of a mosque) respectively. Note the different colour scheme used for the letters board compared with that used today.

The very first Countdown ‘letters game’ produced this selection of consonants and vowels – T, N, E, M, A, R, H, I, B – of which the two contestants were able to think of two seven-letter words ‘raiment’ (an item of clothing) and ‘minaret’ (a thin tower that’s part of a mosque) respectively. Note the different colour scheme used for the letters board compared with that used today.

There were other notable differences between Countdown when it first launched and the same show as it appears today; the contestants do not have name labels and there were two guests in ‘dictionary corner’ as well as Carol Vorderman on hand to make sure that everything ran smoothly.

There were other notable differences between Countdown when it first launched and the same show as it appears today; the contestants do not have name labels and there were two guests in ‘dictionary corner’ as well as Carol Vorderman on hand to make sure that everything ran smoothly.

Another difference between Channel 4 and the other channels was that all programmes were shown across England, Scotland and Northern Ireland, but commercials could either be shown nationally or in specific regional areas (based on the ITV regions). The first commercial to be shown on the new channel was for the Vauxhall Cavalier 1600 GLS.

Another difference between Channel 4 and the other channels was that all programmes were shown across England, Scotland and Northern Ireland, but commercials could either be shown nationally or in specific regional areas (based on the ITV regions). The first commercial to be shown on the new channel was for the Vauxhall Cavalier 1600 GLS.

Channel 4, like BBC2, got off to a shaky start but for different reasons. A disagreement concerning actor’s pay for commercials shown on the fledgling network resulted in an industrial dispute that prevented actors from appearing ‘on camera’ in commercials. This resulted in either a small number of commercials being shown or no commercials at all (depending on the region), at least until the dispute was resolved. Wales has a separate service called S4C with its own Welsh language programming (as well as showing programmes from Channel 4) which had launched the previous day.

Channel 4, like BBC2, got off to a shaky start but for different reasons. A disagreement concerning actor’s pay for commercials shown on the fledgling network resulted in an industrial dispute that prevented actors from appearing ‘on camera’ in commercials. This resulted in either a small number of commercials being shown or no commercials at all (depending on the region), at least until the dispute was resolved. Wales has a separate service called S4C with its own Welsh language programming (as well as showing programmes from Channel 4) which had launched the previous day.

Channel 4 transmitted programmes in the evenings only to begin with, so Channel 4’s test card was a familiar sight for viewers tuning in during the morning and daytime. Unlike BBC2 a new television set was not mandatory, and the fact that the UK UHF transmitter network had from the outset been designed to offer four channels meant that no new aerial was required. Also unlike previous channel launches most of the transmitters were already set up so most of the population could receive the channel (apart from some remote areas).

Channel 4 transmitted programmes in the evenings only to begin with, so Channel 4’s test card was a familiar sight for viewers tuning in during the morning and daytime. Unlike BBC2 a new television set was not mandatory, and the fact that the UK UHF transmitter network had from the outset been designed to offer four channels meant that no new aerial was required. Also unlike previous channel launches most of the transmitters were already set up so most of the population could receive the channel (apart from some remote areas).

Various ITV franchises made programming contributions to the Channel 4 (and S4C) schedule alongside independent producers, including hard-hitting drama Walter produced by Central Television, Countdown produced by Yorkshire Television, 4 What Its Worth produced by Thames Television, amongst numerous others.

Various ITV franchises made programming contributions to the Channel 4 (and S4C) schedule alongside independent producers, including hard-hitting drama Walter produced by Central Television, Countdown produced by Yorkshire Television, 4 What Its Worth produced by Thames Television, amongst numerous others.

The new channel tried out some brave programming ideas in its early years. The Friday Alternative was a hard-hitting politically controversial current affairs show with some key differences; no presenters were visible, there was a left-of-centre political bias and it made heavy use of computer animation between video footage. Indeed The Friday Alternative proved to be so controversial it triggered a row between Channel 4 News producer ITN and Channel 4, forcing the channel into commissioning Diverse Reports as a replacement instead.

The new channel tried out some brave programming ideas in its early years. The Friday Alternative was a hard-hitting politically controversial current affairs show with some key differences; no presenters were visible, there was a left-of-centre political bias and it made heavy use of computer animation between video footage. Indeed The Friday Alternative proved to be so controversial it triggered a row between Channel 4 News producer ITN and Channel 4, forcing the channel into commissioning Diverse Reports as a replacement instead.

Channel 4 News, the 50 minute-long peak time news bulletin along with (perhaps amazingly) Countdown are the only two survivors of Channel 4’s original schedule that continue to be shown to this day. Early critics of the channel dubbed it “Channel Bore” or “Channel Snore”, though it’s naturally easy to knock something if it’s trying to be different.

Channel 4 News, the 50 minute-long peak time news bulletin along with (perhaps amazingly) Countdown are the only two survivors of Channel 4’s original schedule that continue to be shown to this day. Early critics of the channel dubbed it “Channel Bore” or “Channel Snore”, though it’s naturally easy to knock something if it’s trying to be different.

As well as all the arty experimental programming there were much more down to earth offerings like the soap opera Brookside produced by independent production company Mersey Television. Brookside used its own private housing estate as a set, which was unusual for a drama series at that time as opposed to the more normal practice of using a constructed set in a large television studio which gets dismantled and stored away when not in use, but for continuing drama like Brookside, Coronation Street or EastEnders, a permanent set makes a lot more sense. When Brookside came to an end in 2006, the Brookside Close properties were renovated and sold off as private properties, enabling anyone with enough money to actually live in a piece of televisual history.

As well as all the arty experimental programming there were much more down to earth offerings like the soap opera Brookside produced by independent production company Mersey Television. Brookside used its own private housing estate as a set, which was unusual for a drama series at that time as opposed to the more normal practice of using a constructed set in a large television studio which gets dismantled and stored away when not in use, but for continuing drama like Brookside, Coronation Street or EastEnders, a permanent set makes a lot more sense. When Brookside came to an end in 2006, the Brookside Close properties were renovated and sold off as private properties, enabling anyone with enough money to actually live in a piece of televisual history.

Another very popular programme shown during the first few years of the channel’s life was Treasure Hunt, a quiz show presented by Kenneth Kendall that featured two contestants in a TV studio with a library of reference books to help them find and solve clues that could be found within a particular geographical area and within a 45 minute timescale that ultimately led to a cash prize if they were successful.

Another very popular programme shown during the first few years of the channel’s life was Treasure Hunt, a quiz show presented by Kenneth Kendall that featured two contestants in a TV studio with a library of reference books to help them find and solve clues that could be found within a particular geographical area and within a 45 minute timescale that ultimately led to a cash prize if they were successful.

Each Treasure Hunt clue consisted of a card with a printed riddle that gave cryptic details of a location where the next clue could be found; the first clue was read out in the studio at the start of the game and the contestants then had 45 minutes to find the remaining clues that were usually positioned miles apart from each other in different locations, meaning that the contestants had to solve each clue using reference books in the studio and then give verbal instructions to a ‘skyrunner’ (Anneka Rice, later Annabel Croft) via an audio link without any form of visual assistance between the two in order to direct the skyrunner to the location where the next clue is hopefully located.

Each Treasure Hunt clue consisted of a card with a printed riddle that gave cryptic details of a location where the next clue could be found; the first clue was read out in the studio at the start of the game and the contestants then had 45 minutes to find the remaining clues that were usually positioned miles apart from each other in different locations, meaning that the contestants had to solve each clue using reference books in the studio and then give verbal instructions to a ‘skyrunner’ (Anneka Rice, later Annabel Croft) via an audio link without any form of visual assistance between the two in order to direct the skyrunner to the location where the next clue is hopefully located.

Treasure Hunt’s skyrunner had the use of a helicopter to quickly travel to various locations, though inevitably she usually had to do some running and/or borrow other forms of transport in order to actually get to the clue in question from the helicopter landing site. A map on the studio wall showed the approximate location of the helicopter at any given point, and the remaining time in minutes:seconds was often displayed on the screen, with the clock stopping for a while as soon as each clue was found. All the clues had to be solved before the clock reached zero, though there was an additional clue located nearby for a bonus prize if there was still sufficient time remaining (something that almost never happened).

Treasure Hunt’s skyrunner had the use of a helicopter to quickly travel to various locations, though inevitably she usually had to do some running and/or borrow other forms of transport in order to actually get to the clue in question from the helicopter landing site. A map on the studio wall showed the approximate location of the helicopter at any given point, and the remaining time in minutes:seconds was often displayed on the screen, with the clock stopping for a while as soon as each clue was found. All the clues had to be solved before the clock reached zero, though there was an additional clue located nearby for a bonus prize if there was still sufficient time remaining (something that almost never happened).

This style of promotion was used by Channel 4 during 1984, featuring an Orwellian “Big Brother”-style stone slab with added ‘4’ logo which appeared at the end. A wide variety of imaginative programming appeared on the channel during 1984, including Let’s Parlez Franglais (an adaptation of Miles Kington’s magazine feature), Night Beat News (a newsroom comedy also produced in a Welsh language version), and a television opera entitled Perfect Lives. Daytime programming also commenced in 1984 with Channel 4 Racing.

This style of promotion was used by Channel 4 during 1984, featuring an Orwellian “Big Brother”-style stone slab with added ‘4’ logo which appeared at the end. A wide variety of imaginative programming appeared on the channel during 1984, including Let’s Parlez Franglais (an adaptation of Miles Kington’s magazine feature), Night Beat News (a newsroom comedy also produced in a Welsh language version), and a television opera entitled Perfect Lives. Daytime programming also commenced in 1984 with Channel 4 Racing.

By the mid 1980s programmes such as The Word and The Last Resort gained notoriety and media coverage, making Mark Lamarr and the sharp-suited Jonathan Ross stars (among other people). What started life as Friday Live grew into Saturday Night Live was instrumental in changing the whole face of British comedy, launching a whole selection of ‘alternative’ comedians such as Ben Elton (who presented the show), Harry Enfield and Jo Brand. Channel 4 has also commissioned films such as My Beautiful Launderette, Four Weddings and a Funeral, and Slumdog Millionaire. The ‘youth’ show Network Seven was hugely influential in relation to programme production trends, even though the show itself had only a very small audience.

By the mid 1980s programmes such as The Word and The Last Resort gained notoriety and media coverage, making Mark Lamarr and the sharp-suited Jonathan Ross stars (among other people). What started life as Friday Live grew into Saturday Night Live was instrumental in changing the whole face of British comedy, launching a whole selection of ‘alternative’ comedians such as Ben Elton (who presented the show), Harry Enfield and Jo Brand. Channel 4 has also commissioned films such as My Beautiful Launderette, Four Weddings and a Funeral, and Slumdog Millionaire. The ‘youth’ show Network Seven was hugely influential in relation to programme production trends, even though the show itself had only a very small audience.

Channel 4 has never been afraid to be controversial. In 1987 the channel decided to experiment with using what was known as the ‘red triangle’; the idea being was that the triangle would be displayed in the top left hand corner of the screen throughout programmes that featured scenes containing violence or explicit sexual content, effectively serving as a content warning. Opponents to this idea said that this would be an excuse to show even more sex and violence, and viewing figures for programmes that featured the red triangle conversely went up. Within months the whole experiment was quietly dropped.

Channel 4 has never been afraid to be controversial. In 1987 the channel decided to experiment with using what was known as the ‘red triangle’; the idea being was that the triangle would be displayed in the top left hand corner of the screen throughout programmes that featured scenes containing violence or explicit sexual content, effectively serving as a content warning. Opponents to this idea said that this would be an excuse to show even more sex and violence, and viewing figures for programmes that featured the red triangle conversely went up. Within months the whole experiment was quietly dropped.

The Open College was a short-lived attempt to replicate the higher education success of the Open University on Channel 4, and to this end there was an agreement between the Open College – a new educational entity independent of Channel 4 that was created by the government of the day – and Channel 4 to transmit educational programmes from 1988 onwards with Channel 4 providing assistance in terms of resources and time to the approximate value of £1m per year. Open College programmes included Make It Count presented by Fred Harris, but unlike its Open University counterpart, Open College proved to be a failure and the project was soon abandoned.

The Open College was a short-lived attempt to replicate the higher education success of the Open University on Channel 4, and to this end there was an agreement between the Open College – a new educational entity independent of Channel 4 that was created by the government of the day – and Channel 4 to transmit educational programmes from 1988 onwards with Channel 4 providing assistance in terms of resources and time to the approximate value of £1m per year. Open College programmes included Make It Count presented by Fred Harris, but unlike its Open University counterpart, Open College proved to be a failure and the project was soon abandoned.

During the Christmas period in 1990 Channel 4 used this ‘psychedelic four’ with flashing colours as a special ident. As well as being controversial, Channel 4 produces the usual quizzes, soap operas, current affairs, etc., that can be found on other mainstream channels therefore catering for a very wide cross section of the population as a result.

During the Christmas period in 1990 Channel 4 used this ‘psychedelic four’ with flashing colours as a special ident. As well as being controversial, Channel 4 produces the usual quizzes, soap operas, current affairs, etc., that can be found on other mainstream channels therefore catering for a very wide cross section of the population as a result.

In the 1990s Channel 4 started a continuous 24-hour service, and then in 1997 controversially ditched its original ‘coloured 4’ in favour of using a white ‘4’ symbol in conjunction with either circles or squares, as shown here. This was also one of the first examples of the use of real people as part of idents as opposed to showing just a symbol or static drawing of some description; an idea which was to be later copied by many other broadcasters.

In the 1990s Channel 4 started a continuous 24-hour service, and then in 1997 controversially ditched its original ‘coloured 4’ in favour of using a white ‘4’ symbol in conjunction with either circles or squares, as shown here. This was also one of the first examples of the use of real people as part of idents as opposed to showing just a symbol or static drawing of some description; an idea which was to be later copied by many other broadcasters.

The change did not meet universal acclaim – indeed Channel 4’s image was soon to change again much sooner than expected (see below) due to a perceived unpopularity of its new circles-based identity. On January 1 1999 Channel 4 stopped promoting ITV programmes (and vice versa) as the ties between ITV and Channel 4 were finally cut – Channel 4 was now effectively an independent broadcaster.

The change did not meet universal acclaim – indeed Channel 4’s image was soon to change again much sooner than expected (see below) due to a perceived unpopularity of its new circles-based identity. On January 1 1999 Channel 4 stopped promoting ITV programmes (and vice versa) as the ties between ITV and Channel 4 were finally cut – Channel 4 was now effectively an independent broadcaster.

Out with the old, in with the new – Channel 4 introduced its second image ‘makeover’ on 2 April 1999. The unloved circles were ditched in favour of a simple square-shaped logo in combination with scrolling bands of colour; at the same time Channel 4 controversially also tried using a DOG (digitally originated graphic) on its digital feed, meaning that ONdigital and SkyDigital viewers of the channel are treated to a permanent on-screen symbol similar to that used by Channel 5 at the time. This however was later removed because of complaints from viewers, though Channel 4 HD has an on-screen logo presumably to help promote/distinguish the high definition service from its standard definition channel.

Out with the old, in with the new – Channel 4 introduced its second image ‘makeover’ on 2 April 1999. The unloved circles were ditched in favour of a simple square-shaped logo in combination with scrolling bands of colour; at the same time Channel 4 controversially also tried using a DOG (digitally originated graphic) on its digital feed, meaning that ONdigital and SkyDigital viewers of the channel are treated to a permanent on-screen symbol similar to that used by Channel 5 at the time. This however was later removed because of complaints from viewers, though Channel 4 HD has an on-screen logo presumably to help promote/distinguish the high definition service from its standard definition channel.

Compare and contrast: this picture was taken from the end of a programme trailer that was shown just before the April 1999 changes were introduced to the channel. The old-style ‘4 in a circle’ is just visible in the top right hand corner of the picture.

Compare and contrast: this picture was taken from the end of a programme trailer that was shown just before the April 1999 changes were introduced to the channel. The old-style ‘4 in a circle’ is just visible in the top right hand corner of the picture.

And this picture was taken from the end of the revised style of trailer for exactly the same programme. Note that the screen is now essentially divided into two areas, with the larger left area being free for the display of programme information whilst maintaining the logo on the right side of the screen.

And this picture was taken from the end of the revised style of trailer for exactly the same programme. Note that the screen is now essentially divided into two areas, with the larger left area being free for the display of programme information whilst maintaining the logo on the right side of the screen.

Since the ‘square’ look was introduced, subtle changes were subsequently made; at one point the ‘4’ square occasionally flipped across the screen into position, though in other respects the presentation had changed relatively little apart from the introduction of ‘split screens’ at the end of programmes along with ‘now and next’ menus. (Sometimes background images were used behind the moving lines for idents as in this example.) In July 2000, Channel 4 introduced a brand new reality TV show based in a house containing people who are continually watched by cameras and aren’t allowed to leave until they are evicted, namely Big Brother.

Since the ‘square’ look was introduced, subtle changes were subsequently made; at one point the ‘4’ square occasionally flipped across the screen into position, though in other respects the presentation had changed relatively little apart from the introduction of ‘split screens’ at the end of programmes along with ‘now and next’ menus. (Sometimes background images were used behind the moving lines for idents as in this example.) In July 2000, Channel 4 introduced a brand new reality TV show based in a house containing people who are continually watched by cameras and aren’t allowed to leave until they are evicted, namely Big Brother.

The last day of 2004 saw the launch of Channel 4’s new ident package, which essentially saw the return of the Channel 4 logo building up in three dimensions, except this time the logo is formed using building blocks comprising of abstract pieces of landscape such as hedges, concrete blocks, road signs or bales of hay for a surreal effect as the sequence progresses.

The last day of 2004 saw the launch of Channel 4’s new ident package, which essentially saw the return of the Channel 4 logo building up in three dimensions, except this time the logo is formed using building blocks comprising of abstract pieces of landscape such as hedges, concrete blocks, road signs or bales of hay for a surreal effect as the sequence progresses.

Other changes were introduced at the same time including a new look for Channel 4 News (essentially swapping its black and purple colour scheme for new titles and studio appearance in white and blue colours) as well as two new styles of programme promotion, though some minor tweaks were made to Channel 4’s presentation soon after launch. Also note that Channel 4 News was one of the last regularly-broadcast programmes shown on one the main five channels to switch over to widescreen broadcasting as opposed to using the older 4:3 standard, presumably due to cost reasons and/or various other news sources still providing video in the 4:3 aspect ratio at the time.

Other changes were introduced at the same time including a new look for Channel 4 News (essentially swapping its black and purple colour scheme for new titles and studio appearance in white and blue colours) as well as two new styles of programme promotion, though some minor tweaks were made to Channel 4’s presentation soon after launch. Also note that Channel 4 News was one of the last regularly-broadcast programmes shown on one the main five channels to switch over to widescreen broadcasting as opposed to using the older 4:3 standard, presumably due to cost reasons and/or various other news sources still providing video in the 4:3 aspect ratio at the time.

For a week in 2010, Channel 4 jumped on an emerging but short-lived bandwagon for 3D television with a special week of programmes featuring old 3D film footage taken of The Queen and various other people, places and objects. The experiment was essentially similar to the 3D experiments previously conducted by ITV franchise TVS in 1982 which required viewers to wear cardboard glasses with specially-tinted cellophane lenses that were given away with each copy of the TV Times, except that the colour tints used in the Channel 4 experiment were different therefore you couldn’t reuse the same glasses, so you most likely had to obtain new glasses that were made available from branches of Sainsbury’s supermarkets (and a few other places) in order to watch those broadcasts.

For a week in 2010, Channel 4 jumped on an emerging but short-lived bandwagon for 3D television with a special week of programmes featuring old 3D film footage taken of The Queen and various other people, places and objects. The experiment was essentially similar to the 3D experiments previously conducted by ITV franchise TVS in 1982 which required viewers to wear cardboard glasses with specially-tinted cellophane lenses that were given away with each copy of the TV Times, except that the colour tints used in the Channel 4 experiment were different therefore you couldn’t reuse the same glasses, so you most likely had to obtain new glasses that were made available from branches of Sainsbury’s supermarkets (and a few other places) in order to watch those broadcasts.

Ever since Channel 4 decided to get rid of Big Brother from its schedule in 2009 (last broadcast in 2010 on Channel 4), there has been a dilemma of exactly what programming to replace it with, especially as Big Brother and Celebrity Big Brother occupied so much of the schedule. A new weekly series looking back at the week’s events from a comic perspective – 10 O’Clock Live – was introduced in 2012, with other comedy offerings such as Stand Up for the Week and panel game 8 out of 10 Cats forming part of the schedule. The controversial Big Fat Gypsy Weddings reality series and its spinoffs generated lots of publicity but not all of it was positive, therefore those have somewhat inevitably been cancelled as well; other reality shows include One Born Every Minute, The Secret Millionaire, and the controversially-titled The Undateables, as well as educational series like Embarrassing Bodies and How Britain Worked. However Channel 4 has thankfully commissioned a selection of high quality drama series that have partially helped to restore it former reputation for quality programming, namely series like Black Mirror which somewhat distorts reality to make a satirical point, Complicit and the US import Homeland.

Ever since Channel 4 decided to get rid of Big Brother from its schedule in 2009 (last broadcast in 2010 on Channel 4), there has been a dilemma of exactly what programming to replace it with, especially as Big Brother and Celebrity Big Brother occupied so much of the schedule. A new weekly series looking back at the week’s events from a comic perspective – 10 O’Clock Live – was introduced in 2012, with other comedy offerings such as Stand Up for the Week and panel game 8 out of 10 Cats forming part of the schedule. The controversial Big Fat Gypsy Weddings reality series and its spinoffs generated lots of publicity but not all of it was positive, therefore those have somewhat inevitably been cancelled as well; other reality shows include One Born Every Minute, The Secret Millionaire, and the controversially-titled The Undateables, as well as educational series like Embarrassing Bodies and How Britain Worked. However Channel 4 has thankfully commissioned a selection of high quality drama series that have partially helped to restore it former reputation for quality programming, namely series like Black Mirror which somewhat distorts reality to make a satirical point, Complicit and the US import Homeland.

Following on from the hugely successful London 2012 Olympic Games would be a daunting task for anyone, but a combination of goodwill and the promotional skills of Channel 4 turned the following Paralympic Games into a huge success likewise, no doubt helping to make stadium events a sell-out (for the first time in Paralympic history) and generally raising the profile of various sports and competitors. A late evening programme shown during the Games entitled The Last Leg, presented by comedian Adam Hills alongside television newcomers Alex Brooker and Josh Widdecombe who discussed the Games and interviewed Paralympic athletes, became so successful on its own merits it was recommissioned after the Games as a comedy review of the week with celebrity guests. March 2013 saw the introduction of Gogglebox; a series showing families watching and talking about various television programmes in their own homes, which proved to be popular therefore inevitably spawned variants such as Gogglesprogs (featuring children) in 2015 and a one-off ‘Brexit Special’ in 2016.

Following on from the hugely successful London 2012 Olympic Games would be a daunting task for anyone, but a combination of goodwill and the promotional skills of Channel 4 turned the following Paralympic Games into a huge success likewise, no doubt helping to make stadium events a sell-out (for the first time in Paralympic history) and generally raising the profile of various sports and competitors. A late evening programme shown during the Games entitled The Last Leg, presented by comedian Adam Hills alongside television newcomers Alex Brooker and Josh Widdecombe who discussed the Games and interviewed Paralympic athletes, became so successful on its own merits it was recommissioned after the Games as a comedy review of the week with celebrity guests. March 2013 saw the introduction of Gogglebox; a series showing families watching and talking about various television programmes in their own homes, which proved to be popular therefore inevitably spawned variants such as Gogglesprogs (featuring children) in 2015 and a one-off ‘Brexit Special’ in 2016.

In September 2015 Channel 4 introduced a new and highly abstract on-screen identity featuring the blocks that make up its logo appearing in different forms, using short computer-generated animated sequences; four of these created ident sequences (one shown before each programme) formed an entirely fictional ‘story’. Pictured here is an abstract ‘clock’ animation which immediately preceded the Channel 4 News at 7pm; the hidden clock hands ‘twitched’ but didn’t actually rotate though the blocks themselves did move clockwise once each second. Channel 4’s logo only occasionally appeared in its complete form at certain points between programmes.

In September 2015 Channel 4 introduced a new and highly abstract on-screen identity featuring the blocks that make up its logo appearing in different forms, using short computer-generated animated sequences; four of these created ident sequences (one shown before each programme) formed an entirely fictional ‘story’. Pictured here is an abstract ‘clock’ animation which immediately preceded the Channel 4 News at 7pm; the hidden clock hands ‘twitched’ but didn’t actually rotate though the blocks themselves did move clockwise once each second. Channel 4’s logo only occasionally appeared in its complete form at certain points between programmes.

By 2017 Channel 4 introduced fresh computer-generated idents that are more ‘conventional’ in nature, replacing the previous four animated story sequences but keeping most of the rest of the channel’s presentation package as introduced in 2015. They all feature a cartoon figure made out of blocks that does various things, this time accompanied by an acoustic guitar version of the Fourscore theme as originally used back in 1982. 2017 also saw the introduction of The Great British Bake-Off to Channel 4; a baking competition series made by Love Productions but originally commissioned and shown by the BBC. However Channel 4 won the rights to The Great British Bake-Off after a furious bidding war triggered when Love Productions decided that it may be better off moving the popular format to a rival broadcaster.

By 2017 Channel 4 introduced fresh computer-generated idents that are more ‘conventional’ in nature, replacing the previous four animated story sequences but keeping most of the rest of the channel’s presentation package as introduced in 2015. They all feature a cartoon figure made out of blocks that does various things, this time accompanied by an acoustic guitar version of the Fourscore theme as originally used back in 1982. 2017 also saw the introduction of The Great British Bake-Off to Channel 4; a baking competition series made by Love Productions but originally commissioned and shown by the BBC. However Channel 4 won the rights to The Great British Bake-Off after a furious bidding war triggered when Love Productions decided that it may be better off moving the popular format to a rival broadcaster.

They say that restaurant critics make lousy chefs…but do television critics make lousy television? Victor Lewis-Smith is an established television critic (for the London Evening Standard) as well as writing for several other publications, and in the past Lewis-Smith had presented TV programmes such Inside Victor Lewis-Smith plus features within other shows such as BBC2’s TV Hell. His newspaper columns don’t just cover television but also nostalgia, so it’s only logical that he should also have a strong interest in television nostalgia.

They say that restaurant critics make lousy chefs…but do television critics make lousy television? Victor Lewis-Smith is an established television critic (for the London Evening Standard) as well as writing for several other publications, and in the past Lewis-Smith had presented TV programmes such Inside Victor Lewis-Smith plus features within other shows such as BBC2’s TV Hell. His newspaper columns don’t just cover television but also nostalgia, so it’s only logical that he should also have a strong interest in television nostalgia.

From this you might have deduced that TV Offal pokes fun not only at programmes but also at programming formats and ‘celebrities’, as well as anything else that could related to television and broadcasting culture such as test cards and ident (station identification) sequences. Despite the parodying tone, it becomes rapidly self-evident that Victor himself actually revels in these ephemera of TV culture, though it’s equally obvious that he really means it when he mocks celebrities such as Noel Edmonds or Vanessa Feltz. The audio used in the link sequences is almost uniquely (for television) styled in the form of radio jingles, notably jingles specially commissioned from the world-famous American jingle producers JAM.

From this you might have deduced that TV Offal pokes fun not only at programmes but also at programming formats and ‘celebrities’, as well as anything else that could related to television and broadcasting culture such as test cards and ident (station identification) sequences. Despite the parodying tone, it becomes rapidly self-evident that Victor himself actually revels in these ephemera of TV culture, though it’s equally obvious that he really means it when he mocks celebrities such as Noel Edmonds or Vanessa Feltz. The audio used in the link sequences is almost uniquely (for television) styled in the form of radio jingles, notably jingles specially commissioned from the world-famous American jingle producers JAM. It seemed that viewers and critics other than Victor himself liked the pilot show, so Channel 4 went ahead with commissioning a series of six half-hour programmes which ran from May 22nd 1998, shown on Friday evenings at 11 pm. Late night Channel 4 is not exactly viewing suitable for children (as programmes such as Eurotrash or The Word have graphically illustrated), so TV Offal was able to use this scheduling to its advantage in order to show the sort of things that would have made ‘clean-up tv’ campaigner Mary Whitehouse reach for the typewriter…

It seemed that viewers and critics other than Victor himself liked the pilot show, so Channel 4 went ahead with commissioning a series of six half-hour programmes which ran from May 22nd 1998, shown on Friday evenings at 11 pm. Late night Channel 4 is not exactly viewing suitable for children (as programmes such as Eurotrash or The Word have graphically illustrated), so TV Offal was able to use this scheduling to its advantage in order to show the sort of things that would have made ‘clean-up tv’ campaigner Mary Whitehouse reach for the typewriter… Much of the source material used by TV Offal comes from a little-known (outside of the TV industry) phenomenon known as ‘Christmas tapes’. These are unofficial compilations of programme and continuity-related material made by TV station staff in their spare time which often comprised of a collection of ‘outtakes’ (presenters fluffing their lines, etc.) compiled from such incidents recorded during the previous year but also may include clips specially recorded for the tape, originally intended for the staff’s own amusement only and not for transmission; the clip showing the Rainbow (kids’ TV show) team letting off steam with ‘the bad language’ being a prime example. The excerpt used in the pilot episode came from a Christmas 1978 tape produced by Thames Television staff.

Much of the source material used by TV Offal comes from a little-known (outside of the TV industry) phenomenon known as ‘Christmas tapes’. These are unofficial compilations of programme and continuity-related material made by TV station staff in their spare time which often comprised of a collection of ‘outtakes’ (presenters fluffing their lines, etc.) compiled from such incidents recorded during the previous year but also may include clips specially recorded for the tape, originally intended for the staff’s own amusement only and not for transmission; the clip showing the Rainbow (kids’ TV show) team letting off steam with ‘the bad language’ being a prime example. The excerpt used in the pilot episode came from a Christmas 1978 tape produced by Thames Television staff. Every TV Offal featured one or two “Kamikaze Karaoke” sketches, whereby some of the most famous popular/classical music acts are seen performing, but their voices substituted with singing that is off-key/has different lyrics/etc., superimposed upon the same or similar musical backing. Guaranteed to bring the most egoistical superstar crashing down to earth, singers and acts which had been given the “This is what he sounds like to me” treatment included Pavarotti, Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley, Elton John, Bob Marley, Nigel Kennedy, Vanessa-Mae and that Manchester foursome Oasis.

Every TV Offal featured one or two “Kamikaze Karaoke” sketches, whereby some of the most famous popular/classical music acts are seen performing, but their voices substituted with singing that is off-key/has different lyrics/etc., superimposed upon the same or similar musical backing. Guaranteed to bring the most egoistical superstar crashing down to earth, singers and acts which had been given the “This is what he sounds like to me” treatment included Pavarotti, Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley, Elton John, Bob Marley, Nigel Kennedy, Vanessa-Mae and that Manchester foursome Oasis. Probably the most controversial of TV Offal‘s regular features is the Gay Daleks: “They’re camp! They exterminate! Better watch your backs! It’s the Gay Daleks!” You either feel that the sketches are crude, tasteless and offensive, or they’re a splendid parody of both the Daleks and of gay cultural stereotypes; late night Channel 4 viewers (on the whole) would interpret them as the latter which is probably just as well given the content. Apparently they were popular with the gay community, though later attempts to produce a cartoon series based on the Gay Daleks did not materialise due to rights issues involving the Terry Nation estate.

Probably the most controversial of TV Offal‘s regular features is the Gay Daleks: “They’re camp! They exterminate! Better watch your backs! It’s the Gay Daleks!” You either feel that the sketches are crude, tasteless and offensive, or they’re a splendid parody of both the Daleks and of gay cultural stereotypes; late night Channel 4 viewers (on the whole) would interpret them as the latter which is probably just as well given the content. Apparently they were popular with the gay community, though later attempts to produce a cartoon series based on the Gay Daleks did not materialise due to rights issues involving the Terry Nation estate. Another semi-regular feature that straddles the commercial break is “Assassination of the Week”. This sketch parodies the voyeurism that certain programmes seem to exhibit, namely, before the commercial break an assassination attempt is shown, and viewers are invited to guess “did they live or are they worm-food?”. After the break the rest of the film is shown and the answer is given, though there was a twist when the assassination of JFK was covered. Other politicians featured included Imelda Marcos, the woman which had a very large shoe collection.

Another semi-regular feature that straddles the commercial break is “Assassination of the Week”. This sketch parodies the voyeurism that certain programmes seem to exhibit, namely, before the commercial break an assassination attempt is shown, and viewers are invited to guess “did they live or are they worm-food?”. After the break the rest of the film is shown and the answer is given, though there was a twist when the assassination of JFK was covered. Other politicians featured included Imelda Marcos, the woman which had a very large shoe collection. TV Offal often featured “The Pilots that Crashed”; one-off programmes that never got any further than the pilot episode or shows that had a very limited run. Perhaps controversially, the show featured “The Development of the Television Test Card” in show 2 which wasn’t a failed pilot programme; indeed it was a one-off show (made in 1985) aimed at a specialist audience as reference material therefore it was never intended to be commissioned as a broadcast series. But it featured one of Victor’s favourite subjects (as anyone seeing any earlier material of his would testify) so he couldn’t possibly ignore it!

TV Offal often featured “The Pilots that Crashed”; one-off programmes that never got any further than the pilot episode or shows that had a very limited run. Perhaps controversially, the show featured “The Development of the Television Test Card” in show 2 which wasn’t a failed pilot programme; indeed it was a one-off show (made in 1985) aimed at a specialist audience as reference material therefore it was never intended to be commissioned as a broadcast series. But it featured one of Victor’s favourite subjects (as anyone seeing any earlier material of his would testify) so he couldn’t possibly ignore it! TV Offal regularly featured clips from the archives of student or hospital television stations, often featuring celebrities either before they became famous or making a guest appearence. Famous people featured included Michaela Strachan, Phillippa Forrester, and Christopher Biggins. The picture is taken from the ident used in 1969 of STOIC – Student Television of Imperial College (London).

TV Offal regularly featured clips from the archives of student or hospital television stations, often featuring celebrities either before they became famous or making a guest appearence. Famous people featured included Michaela Strachan, Phillippa Forrester, and Christopher Biggins. The picture is taken from the ident used in 1969 of STOIC – Student Television of Imperial College (London). A TV Offal show wouldn’t be complete without one of Victor Lewis-Smith’s “specialities”, the wind-up phone call. He calls a famous person or organisation pretending to be someone else, with either hilarious or deeply embarrassing results. “Victims” included Carlton Television in the first show, the late Hughie Green and Mary Whitehouse. However the alleged ‘call’ to Mary Whitehouse landed Victor in a spot of bother, and it’s also interesting to note that phone calls of this nature are no longer permitted to be broadcast on UK television under Ofcom regulations.

A TV Offal show wouldn’t be complete without one of Victor Lewis-Smith’s “specialities”, the wind-up phone call. He calls a famous person or organisation pretending to be someone else, with either hilarious or deeply embarrassing results. “Victims” included Carlton Television in the first show, the late Hughie Green and Mary Whitehouse. However the alleged ‘call’ to Mary Whitehouse landed Victor in a spot of bother, and it’s also interesting to note that phone calls of this nature are no longer permitted to be broadcast on UK television under Ofcom regulations. The show is produced by Victor’s own production company, Associated-Rediffusion Television Ltd., which happens also to be the name of the ITV contractor that served London weekdays from 1955-1968. Victor bought the rights many years ago when it was simply ‘gathering dust’, and he even featured the voice of Redvers Kyle who was a regular continuity announcer for A-R in the 1950s (amongst others), in show 4. There will never be a commercial release (DVD/video download, etc.) of the TV Offal series because producer John Warburton found it difficult enough gaining copyright clearance for many of the clips used simply for television transmission.

The show is produced by Victor’s own production company, Associated-Rediffusion Television Ltd., which happens also to be the name of the ITV contractor that served London weekdays from 1955-1968. Victor bought the rights many years ago when it was simply ‘gathering dust’, and he even featured the voice of Redvers Kyle who was a regular continuity announcer for A-R in the 1950s (amongst others), in show 4. There will never be a commercial release (DVD/video download, etc.) of the TV Offal series because producer John Warburton found it difficult enough gaining copyright clearance for many of the clips used simply for television transmission. So, to paraphrase the “Assassination of the Week” feature, what happened next? The answer is the cleverly-titled Ads Infinitum – two series of ten-minute programmes shown on BBC2 (the first series in 1998), which (as the title suggests) are all about television or cinema adverts. And as for TV Offal itself, the only repeat showings were some compilation programmes (‘the best of’ or ‘the worst of’, depending on your point of view.) subsequently shown on Channel 4. These days Victor Lewis-Smith is occasionally still involved with television production and continues to be a newspaper TV critic and columnist for publications such as Private Eye; recent productions include Alchemists of Sound for BBC Four, You’re Fayed! for Channel 4 and a documentary The Undiscovered Peter Cook for BBC Four featuring some of the satirist’s personal diaries, letters, photographs and recordings.

So, to paraphrase the “Assassination of the Week” feature, what happened next? The answer is the cleverly-titled Ads Infinitum – two series of ten-minute programmes shown on BBC2 (the first series in 1998), which (as the title suggests) are all about television or cinema adverts. And as for TV Offal itself, the only repeat showings were some compilation programmes (‘the best of’ or ‘the worst of’, depending on your point of view.) subsequently shown on Channel 4. These days Victor Lewis-Smith is occasionally still involved with television production and continues to be a newspaper TV critic and columnist for publications such as Private Eye; recent productions include Alchemists of Sound for BBC Four, You’re Fayed! for Channel 4 and a documentary The Undiscovered Peter Cook for BBC Four featuring some of the satirist’s personal diaries, letters, photographs and recordings. Ever wondered how everyday home appliances such as a fridge, fax machine, or central heating operated? Even if you hadn’t, The Secret Life of Machines series set out to explain simply and clearly how these (and more) items perform their functions. Presented by Tim Hunkin (right) and Rex Garrod, three series of programmes were produced for Channel 4 in 1988, 1991 and 1993 (the third series was entitled The Secret Life of the Office); all pictures shown here are taken from The Secret Life of the Television Set which was the last programme in the first series. Other programmes have since been produced that have names prefixed with “The Secret Life of…” (e.g. The Secret Life of the Zoo), but they are unrelated to The Secret Life of Machines/The Secret Life of the Office.

Ever wondered how everyday home appliances such as a fridge, fax machine, or central heating operated? Even if you hadn’t, The Secret Life of Machines series set out to explain simply and clearly how these (and more) items perform their functions. Presented by Tim Hunkin (right) and Rex Garrod, three series of programmes were produced for Channel 4 in 1988, 1991 and 1993 (the third series was entitled The Secret Life of the Office); all pictures shown here are taken from The Secret Life of the Television Set which was the last programme in the first series. Other programmes have since been produced that have names prefixed with “The Secret Life of…” (e.g. The Secret Life of the Zoo), but they are unrelated to The Secret Life of Machines/The Secret Life of the Office. A special feature is the use of (often humourous) cartoons that are used to illustrate ‘moments in history’ which are relevant to the appliance under discussion. This picture is taken from a cartoon used to show the moment when it was discovered that selenium can cause an electrical voltage to change dependent on the amount of light shining on it.

A special feature is the use of (often humourous) cartoons that are used to illustrate ‘moments in history’ which are relevant to the appliance under discussion. This picture is taken from a cartoon used to show the moment when it was discovered that selenium can cause an electrical voltage to change dependent on the amount of light shining on it. Tim Hunkin (the main presenter and architect of the series) may look exactly like the stereotypical image of “the professor”, but contrary to this he presents technology in a very straightforward and easy to understand manner and manages to do so in a way that can keep the interest of both novices and experts alike. His secret is possibly that if you’re not afraid of technology and you understand how an item works you can “deconstruct” an item into its various simpler components, and also avoiding unneccesary complexity when explaining how something operates.

Tim Hunkin (the main presenter and architect of the series) may look exactly like the stereotypical image of “the professor”, but contrary to this he presents technology in a very straightforward and easy to understand manner and manages to do so in a way that can keep the interest of both novices and experts alike. His secret is possibly that if you’re not afraid of technology and you understand how an item works you can “deconstruct” an item into its various simpler components, and also avoiding unneccesary complexity when explaining how something operates. So how did Tim get into television? After gaining a Cambridge degree, he took on a series of bizarre commissions ranging from firework displays to mechanical sculptures. Back in 1972 he had drawn some cartoons for the Cambridge University newspaper Stop Press (the first one was about drawing cows!); this lead to a whole series of witty and factual cartoons for the Sunday Observer magazine colour supplement from 1973 to 1987 entitled “The Rudiments of Wisdom”, covering everything from acids to zoos (they were republished later in a book). Anticipating change at The Observer, Tim developed a proposal for a television series and his agent sent it to Channel 4. The rest, as they say, is history.

So how did Tim get into television? After gaining a Cambridge degree, he took on a series of bizarre commissions ranging from firework displays to mechanical sculptures. Back in 1972 he had drawn some cartoons for the Cambridge University newspaper Stop Press (the first one was about drawing cows!); this lead to a whole series of witty and factual cartoons for the Sunday Observer magazine colour supplement from 1973 to 1987 entitled “The Rudiments of Wisdom”, covering everything from acids to zoos (they were republished later in a book). Anticipating change at The Observer, Tim developed a proposal for a television series and his agent sent it to Channel 4. The rest, as they say, is history. Don’t try this at home kids! (Or for that matter, adults as well!) Who else would probably construct their own plasma lamp using the high voltage line output transformer from an old television set?

Don’t try this at home kids! (Or for that matter, adults as well!) Who else would probably construct their own plasma lamp using the high voltage line output transformer from an old television set? Humour can help make something more memorable, as many academic lecturers are sometimes keen to point out. A cartoon showing that the electronic-scanning Marconi-EMI system cameras (as opposed to the large fixed-position Baird mechanical scanning cameras) were much more versatile by showing someone using one to record a flying aircraft, and then showing the poor camerman being knocked over by the low-flying aircraft!

Humour can help make something more memorable, as many academic lecturers are sometimes keen to point out. A cartoon showing that the electronic-scanning Marconi-EMI system cameras (as opposed to the large fixed-position Baird mechanical scanning cameras) were much more versatile by showing someone using one to record a flying aircraft, and then showing the poor camerman being knocked over by the low-flying aircraft! So what do Tim and Rex do when they’re not making television programmes? Well they make models and other mechanical devices for various organisations such as exhibitions and television programmes, and these were often featured to illustrate concepts throughout the series. This wind-powered mechanical clock was developed for the Liverpool Garden Festival some years ago.

So what do Tim and Rex do when they’re not making television programmes? Well they make models and other mechanical devices for various organisations such as exhibitions and television programmes, and these were often featured to illustrate concepts throughout the series. This wind-powered mechanical clock was developed for the Liverpool Garden Festival some years ago. Tim Hunkin also designs and builds a lot of those ‘hands-on’ museum exhibits that interact in some way with the visitor; he designed this section for the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television in Bradford, Yorkshire. Amongst other commissions he has also developed for the Science Museum in London.

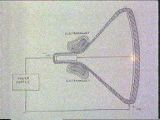

Tim Hunkin also designs and builds a lot of those ‘hands-on’ museum exhibits that interact in some way with the visitor; he designed this section for the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television in Bradford, Yorkshire. Amongst other commissions he has also developed for the Science Museum in London. Here is an example of a display from the Bradford museum, showing how an electron beam generates a spot of light when it hits the phosphor-coated front surface of the cathode-ray tube.

Here is an example of a display from the Bradford museum, showing how an electron beam generates a spot of light when it hits the phosphor-coated front surface of the cathode-ray tube. Tim and Rex are not afraid of using anything unusual to illustrate something that they are trying to explain – here they are using string with ink dots on it to illustrate how a television picture in constructed using scanning lines and dots of varying brightness.

Tim and Rex are not afraid of using anything unusual to illustrate something that they are trying to explain – here they are using string with ink dots on it to illustrate how a television picture in constructed using scanning lines and dots of varying brightness. To conclude the first series they built an amazing funeral pyre consisting of old television sets which were faulty in some way but were not worth repairing. The stack of sets were all switched on when the flames were lit, and as the end credits rolled the TV screens flickered and died in turn as the flames rose higher and higher. However it has now been revealed that they wrongly thought the end credits would be less than a minute long therefore the fire was designed to burn quickly, meaning that they had to make the most out of using a relatively small quantity of film footage.

To conclude the first series they built an amazing funeral pyre consisting of old television sets which were faulty in some way but were not worth repairing. The stack of sets were all switched on when the flames were lit, and as the end credits rolled the TV screens flickered and died in turn as the flames rose higher and higher. However it has now been revealed that they wrongly thought the end credits would be less than a minute long therefore the fire was designed to burn quickly, meaning that they had to make the most out of using a relatively small quantity of film footage. The programmes were mainly Tim Hunkin’s own work, though he had assistants to help him with various tasks such as production. Tim feels that although the shows were popular there was a danger that they were becoming “too formula-based”, so there are no further plans for any more “Secret Life” programmes – however in 1998 he planned to develop a TV series about photography which unfortunately didn’t materialise. Meanwhile he has numerous projects to keep him occupied; he gave a Science Museum talk entitled “Illegal Engineering” which was all about security and safe-cracking, and recent commissions include a Pirate Practice arcade machine installed at Southend Pier in 2012. He also has a “mad arcade of home-made machines & simulator rides” at Southwold Pier in Suffolk entitled “The Under The Pier Show” as well as machines at Novelty Automation based in London. Rex was last seen on the programme Robot Wars as part of a team which lost in a final.

The programmes were mainly Tim Hunkin’s own work, though he had assistants to help him with various tasks such as production. Tim feels that although the shows were popular there was a danger that they were becoming “too formula-based”, so there are no further plans for any more “Secret Life” programmes – however in 1998 he planned to develop a TV series about photography which unfortunately didn’t materialise. Meanwhile he has numerous projects to keep him occupied; he gave a Science Museum talk entitled “Illegal Engineering” which was all about security and safe-cracking, and recent commissions include a Pirate Practice arcade machine installed at Southend Pier in 2012. He also has a “mad arcade of home-made machines & simulator rides” at Southwold Pier in Suffolk entitled “The Under The Pier Show” as well as machines at Novelty Automation based in London. Rex was last seen on the programme Robot Wars as part of a team which lost in a final. Over the years there have been many varieties of quiz show, from the intellectual (such as Call My Bluff) to the unashamedly populist Play Your Cards Right. QD: The Master Game was fundamentally similar to shows such as the mid-1980s TVS-produced Ultra Quiz, though it also had an affinity with the more intellectual shows. To briefly summarise – over five half-hour programmes (shown Monday to Friday on Channel 4 in 1991) an initially large number of contestants take part in a series of intellectual challenges; the number of contestants are reduced through elimination to a more manageable number for the final stages.

Over the years there have been many varieties of quiz show, from the intellectual (such as Call My Bluff) to the unashamedly populist Play Your Cards Right. QD: The Master Game was fundamentally similar to shows such as the mid-1980s TVS-produced Ultra Quiz, though it also had an affinity with the more intellectual shows. To briefly summarise – over five half-hour programmes (shown Monday to Friday on Channel 4 in 1991) an initially large number of contestants take part in a series of intellectual challenges; the number of contestants are reduced through elimination to a more manageable number for the final stages. So what exactly did QD stand for, apart from yet another quiz game? An ongoing competition that took place during the five days when QD: The Master Game was shown was for viewers to guess what QD stood for, with the answer being revealed on Friday. To guess this one required knowledge of Latin and/or access to a Latin dictionary, since QD was an abbreviation for the Latin ‘quinque dies’ (or five days) – though if QD had reminded you of the famous abbreviation QED (quod erat demonstratum) you were probably half way there! This illustrates clearly that QD was not going to be just another ordinary quiz show.

So what exactly did QD stand for, apart from yet another quiz game? An ongoing competition that took place during the five days when QD: The Master Game was shown was for viewers to guess what QD stood for, with the answer being revealed on Friday. To guess this one required knowledge of Latin and/or access to a Latin dictionary, since QD was an abbreviation for the Latin ‘quinque dies’ (or five days) – though if QD had reminded you of the famous abbreviation QED (quod erat demonstratum) you were probably half way there! This illustrates clearly that QD was not going to be just another ordinary quiz show. The presenters were the experienced Tim Brooke-Taylor (who was one of the Goodies – a popular BBC comedy show of the 1970s) and Lisa Aziz, who was the daughter of Khalid Aziz (he was a presenter who had worked for TVS, the ITV company who had also coincidentally produced Ultra Quiz). It seemed obvious that QD: The Master Game‘s format had been influenced by shows like The Krypton Factor along with the aforementioned Ultra Quiz.

The presenters were the experienced Tim Brooke-Taylor (who was one of the Goodies – a popular BBC comedy show of the 1970s) and Lisa Aziz, who was the daughter of Khalid Aziz (he was a presenter who had worked for TVS, the ITV company who had also coincidentally produced Ultra Quiz). It seemed obvious that QD: The Master Game‘s format had been influenced by shows like The Krypton Factor along with the aforementioned Ultra Quiz. The studio set was fairly elaborate and must have cost quite a lot of time and money to construct (Noel Gay Productions must have been confident of QD being commissioned as a full series). This view of the studio gantry shows the large signs showing the days of the week: the appropriate one being lowered into view. The show also used video effects heavily, with captions spinning into view and an elaborate title sequence (which unfortunately we don’t have in its full form).

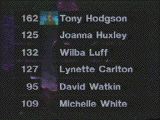

The studio set was fairly elaborate and must have cost quite a lot of time and money to construct (Noel Gay Productions must have been confident of QD being commissioned as a full series). This view of the studio gantry shows the large signs showing the days of the week: the appropriate one being lowered into view. The show also used video effects heavily, with captions spinning into view and an elaborate title sequence (which unfortunately we don’t have in its full form). By Friday (the show from which all of these pictures were taken) the number of contestants had been reduced to six, and all of them remained ‘in play’ in order to decide which person was to receive the £5000 prize.

By Friday (the show from which all of these pictures were taken) the number of contestants had been reduced to six, and all of them remained ‘in play’ in order to decide which person was to receive the £5000 prize. The person with the highest score at the start of Friday’s play (Tony Hodgson) was rarely troubled during the show and went on to win the final prize, though the prize for the contestant who was the most popular with the studio audience had to go to Wilba Luff, who was extrovert yet likeable (Wilba incidentally is a nickname for William). Simply mentioning his name provoked cheers and yelps from the audience; indeed the very concept of “getting to know the contestants” is very much a part of modern ‘reality’ TV formats and QD: The Master Game along with Ultra Quiz employed an “emotional journey” factor as part of their appeal years before programmes like Pop Idol were shown.

The person with the highest score at the start of Friday’s play (Tony Hodgson) was rarely troubled during the show and went on to win the final prize, though the prize for the contestant who was the most popular with the studio audience had to go to Wilba Luff, who was extrovert yet likeable (Wilba incidentally is a nickname for William). Simply mentioning his name provoked cheers and yelps from the audience; indeed the very concept of “getting to know the contestants” is very much a part of modern ‘reality’ TV formats and QD: The Master Game along with Ultra Quiz employed an “emotional journey” factor as part of their appeal years before programmes like Pop Idol were shown. Fingers on buzzers! The challenges were a mixture of practical tests (see below) and general knowledge/memory tests; one which featured in Friday’s show was that the contestants had to try to memorise the contents of a book full of abbreviations – they were then tested on how much of the book they had actually remembered, though in this case some of the questions could be answered if you had good general knowledge skills. An example question: What does IMF stand for? (Answer: International Monetary Fund.)

Fingers on buzzers! The challenges were a mixture of practical tests (see below) and general knowledge/memory tests; one which featured in Friday’s show was that the contestants had to try to memorise the contents of a book full of abbreviations – they were then tested on how much of the book they had actually remembered, though in this case some of the questions could be answered if you had good general knowledge skills. An example question: What does IMF stand for? (Answer: International Monetary Fund.) One of the ongoing challenges during the week was for the contestants to design a graphic logo which incorporated QD and the European flag symbol. No prizes for guessing who won this round…the others sadly didn’t stand much of a chance!

One of the ongoing challenges during the week was for the contestants to design a graphic logo which incorporated QD and the European flag symbol. No prizes for guessing who won this round…the others sadly didn’t stand much of a chance! There must be at least six video copies of QD in existence, since the ‘losers’ (and I’m assuming Tony Hodgson as well) received a video cassette of the entire week’s programmes. The runners-up also each received this neat-looking 10″ television/video combination to play it on. Tony (to win the £5000) then had to answer 30 questions (based on all that he had done during the five days) in three minutes, which he did – but only just.

There must be at least six video copies of QD in existence, since the ‘losers’ (and I’m assuming Tony Hodgson as well) received a video cassette of the entire week’s programmes. The runners-up also each received this neat-looking 10″ television/video combination to play it on. Tony (to win the £5000) then had to answer 30 questions (based on all that he had done during the five days) in three minutes, which he did – but only just. Tony Hodgson (centre) received his cheque for £5000 at the end – he was asked how he would spend the money. He replied that he would possibly buy a computer for educational purposes for his family (sensible chap that he is). We’ve worked out that at the time his options would have been either a 66 MHz 486 DX/2 PC or Apple Mac Quadra 900 4/160 (the latter leaving no change from £4095, and little change for extras such as a single-speed CD-ROM). Overall the general feeling was that both the contestants, the studio audience, and (hopefully) the viewers had enjoyed these five days in 1991.

Tony Hodgson (centre) received his cheque for £5000 at the end – he was asked how he would spend the money. He replied that he would possibly buy a computer for educational purposes for his family (sensible chap that he is). We’ve worked out that at the time his options would have been either a 66 MHz 486 DX/2 PC or Apple Mac Quadra 900 4/160 (the latter leaving no change from £4095, and little change for extras such as a single-speed CD-ROM). Overall the general feeling was that both the contestants, the studio audience, and (hopefully) the viewers had enjoyed these five days in 1991. Despite the enthusiasm shown for the pilot, Channel 4 did not commission a full series; the official reason given (according to Tim Brooke-Taylor) was that it would have cost too much. Unofficially its demise may have been down to simply the fact that the relevant commissioning editor wasn’t too keen on the idea in the first place – it was Bill Cotton who came up with the idea, and his friend Michael Grade just happened to be head of Channel 4. QED. Tim also said that “I loved the scary week and cannot speak highly enough of the contestants and the production team. I also have a copy and am proud of the whole thing. But don’t ask me about commissioning editors.”

Despite the enthusiasm shown for the pilot, Channel 4 did not commission a full series; the official reason given (according to Tim Brooke-Taylor) was that it would have cost too much. Unofficially its demise may have been down to simply the fact that the relevant commissioning editor wasn’t too keen on the idea in the first place – it was Bill Cotton who came up with the idea, and his friend Michael Grade just happened to be head of Channel 4. QED. Tim also said that “I loved the scary week and cannot speak highly enough of the contestants and the production team. I also have a copy and am proud of the whole thing. But don’t ask me about commissioning editors.” Although initially regulated by the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) with financial cross-subsidy from the ITV franchises, Channel 4 was a broadcaster designed to be independent from ITV, but due to a perceived high risk of financial failure such measures were necessary along with ITV franchises providing some of the programming and being responsible for the channel’s advertising sales, effectively leaving Channel 4 to do what it wanted without having to specifically pander to any of its advertisers. Its remit was and still is essentially similar to BBC2, namely producing specialist programmes for a smaller audience as well as popular programmes, though to begin with Channel 4 was unique in that the majority of programmes were commissioned from small independent production companies.