In the days before remote controls you had to get out of your seat to make any adjustments to the television set such as adjusting the volume or changing the channel, etc., with the earliest televisions often only being capable of receiving one or two TV channels that were pre-defined for a particular transmitter by the supplying dealer if not done so at the factory.

In the days before remote controls you had to get out of your seat to make any adjustments to the television set such as adjusting the volume or changing the channel, etc., with the earliest televisions often only being capable of receiving one or two TV channels that were pre-defined for a particular transmitter by the supplying dealer if not done so at the factory.

These manual controls often had a great tactile feel to them, especially the VHF channel selector which usually clicked when the knob was turned, and there were numerous other controls for picture adjustment (usually concealed at the sides or rear) which occasionally had to be adjusted due to valve-based circuitry drifting out of alignment, hence the importance of the test card and tuning signal broadcasts prior to the 1980s because they were used to correctly set up a television receiver.

These manual controls often had a great tactile feel to them, especially the VHF channel selector which usually clicked when the knob was turned, and there were numerous other controls for picture adjustment (usually concealed at the sides or rear) which occasionally had to be adjusted due to valve-based circuitry drifting out of alignment, hence the importance of the test card and tuning signal broadcasts prior to the 1980s because they were used to correctly set up a television receiver.

So what were the shops that sold televisions like in the 1950s? The pictures above show a typical example – this was the era before the advent of the big superstore, so lots of receivers were packed into a relatively small shop space (though some department stores also sold televisions, of course). The brand names are mainly unfamiliar, and there’s a complete absence of anything resembling a video recorder. Only one set is showing a picture, and it is Test Card C which was a very common daytime sight in this period.

So what were the shops that sold televisions like in the 1950s? The pictures above show a typical example – this was the era before the advent of the big superstore, so lots of receivers were packed into a relatively small shop space (though some department stores also sold televisions, of course). The brand names are mainly unfamiliar, and there’s a complete absence of anything resembling a video recorder. Only one set is showing a picture, and it is Test Card C which was a very common daytime sight in this period.

The dawn of commercial television (ITV) in 1955 – TV shops in the London and Midlands had signs like this one in the window as retailers promoted the forthcoming ITV service.

The dawn of commercial television (ITV) in 1955 – TV shops in the London and Midlands had signs like this one in the window as retailers promoted the forthcoming ITV service.

If you already had a TV set and wanted ITV as well…prepare to be converted – at a price, of course. In front is a card promoting Ferguson TV’s. “Fine sets those Ferguson’s” was the slogan used at the time.

If you already had a TV set and wanted ITV as well…prepare to be converted – at a price, of course. In front is a card promoting Ferguson TV’s. “Fine sets those Ferguson’s” was the slogan used at the time.

And talking of Ferguson, here’s a selection of Ferguson TV’s and radio’s from the mid 1950s. Ferguson were taken over by the Thorn-EMI empire, which then sold the brand to Thomson (100% owned by the French government), though Thomson has now ceased to exist in the UK. Brands like Alba, Bush and Murphy are now the preserve of retailers and mail order catalogues who basically just use the name for their own-branded products.

And talking of Ferguson, here’s a selection of Ferguson TV’s and radio’s from the mid 1950s. Ferguson were taken over by the Thorn-EMI empire, which then sold the brand to Thomson (100% owned by the French government), though Thomson has now ceased to exist in the UK. Brands like Alba, Bush and Murphy are now the preserve of retailers and mail order catalogues who basically just use the name for their own-branded products.

There were many more brands of television prior to the 1980s, most of which have long since disappeared altogether or absorbed into multinational companies. Here is a picture of the innards of an Ekco television of the mid 1950s.

There were many more brands of television prior to the 1980s, most of which have long since disappeared altogether or absorbed into multinational companies. Here is a picture of the innards of an Ekco television of the mid 1950s.

Moving forward ten years to 1965, and the introduction of one of the first ‘affordable’ video tape recording machines – the Philips EL3400. It was bulky and used an exposed reel of tape, plus it only recorded in black and white despite colour transmissions being available not long afterwards. It also had no tuner or timer facility, so it was only useful with (sometimes) expensive external ancillary equipment such as a separate television tuner or video camera. However, two years before the EL3400 there was a British recorder advertised for sale called the Telcan that was possibly the world’s first domestic video recorder. It could record approximately 20 minutes of 405 line video and audio onto audio tape; a remarkable feat for relatively primitive technology but was a commercial failure presumably due to the short length of its recordings. Only two examples of the Telcan are known to exist nowadays.

Moving forward ten years to 1965, and the introduction of one of the first ‘affordable’ video tape recording machines – the Philips EL3400. It was bulky and used an exposed reel of tape, plus it only recorded in black and white despite colour transmissions being available not long afterwards. It also had no tuner or timer facility, so it was only useful with (sometimes) expensive external ancillary equipment such as a separate television tuner or video camera. However, two years before the EL3400 there was a British recorder advertised for sale called the Telcan that was possibly the world’s first domestic video recorder. It could record approximately 20 minutes of 405 line video and audio onto audio tape; a remarkable feat for relatively primitive technology but was a commercial failure presumably due to the short length of its recordings. Only two examples of the Telcan are known to exist nowadays.

Compared to the Telcan, the EL3400 was a greater success and certainly had its uses, as a group of dancers watch themselves perform on a large video projection screen. The EL3400 did not come cheap because it used a helical scan recording technique also used by professional recorders like the Ampex Quadraplex (the world’s first broadcast quality video recorder), so it was typically found only in large education establishments or used for industrial applications. Also Japanese companies such as Shibaden and Sony were starting to make their presence felt at this time with recorders like the CV-2000 format reel to reel machines which were soon followed by the U-Matic video cassette that proved popular in the industrial and commercial markets.

Compared to the Telcan, the EL3400 was a greater success and certainly had its uses, as a group of dancers watch themselves perform on a large video projection screen. The EL3400 did not come cheap because it used a helical scan recording technique also used by professional recorders like the Ampex Quadraplex (the world’s first broadcast quality video recorder), so it was typically found only in large education establishments or used for industrial applications. Also Japanese companies such as Shibaden and Sony were starting to make their presence felt at this time with recorders like the CV-2000 format reel to reel machines which were soon followed by the U-Matic video cassette that proved popular in the industrial and commercial markets.

The common face of television in the mid to late 1960s – black and white, dual standard (though lots of single-standard 405 line VHF-only televisions remained in use for many years) with separate controls for 405-line VHF and 625-line UHF transmissions. This was required since from 1964 the new BBC2 service was only available on UHF.

The common face of television in the mid to late 1960s – black and white, dual standard (though lots of single-standard 405 line VHF-only televisions remained in use for many years) with separate controls for 405-line VHF and 625-line UHF transmissions. This was required since from 1964 the new BBC2 service was only available on UHF.

1967 saw the arrival of the first mass produced colour TV’s for the UK market, though their high price and initial lack of colour programming (BBC2 only until 1969, few transmitters provided a colour signal and not all programmes were in colour) ensured slow sales to begin with. The picture shows an HMV Colourmaster which was typical of the sets produced in the late 1960s. Find out more about early colour television on the Colour Television page.

1967 saw the arrival of the first mass produced colour TV’s for the UK market, though their high price and initial lack of colour programming (BBC2 only until 1969, few transmitters provided a colour signal and not all programmes were in colour) ensured slow sales to begin with. The picture shows an HMV Colourmaster which was typical of the sets produced in the late 1960s. Find out more about early colour television on the Colour Television page.

Fast forward to 1972 – though a few lucky buyers may have had access to one in 1971 – and the launch of the first ‘proper’ ‘home’ video recorder with an integrated tuner and timer, the Philips N1500. This close-up view (disregard the Sony machine just visible) shows the sloping front panel with (from left to right) a recording level meter, tape transport controls, and the 1 day, 1 event ‘egg timer’ clock. Each large Philips VCR cassette could record up to 30 or 60 (later 80) minutes; the six channel selector buttons are visible above the transport controls. The only thing to put off a potential purchaser – apart from the relatively short running time – was the steep price tag. However the N1500 was not generally available until the end of 1973; earlier it was only sold to schools and corporate customers, and these customers remained the main purchasers of such an expensive device. The less than 90 minutes maximum recording time would have limited its appeal to wealthy people who weren’t interested in recording long movies, therefore it tended to be only specialist shops and upmarket department stores that stocked the recorder.

Fast forward to 1972 – though a few lucky buyers may have had access to one in 1971 – and the launch of the first ‘proper’ ‘home’ video recorder with an integrated tuner and timer, the Philips N1500. This close-up view (disregard the Sony machine just visible) shows the sloping front panel with (from left to right) a recording level meter, tape transport controls, and the 1 day, 1 event ‘egg timer’ clock. Each large Philips VCR cassette could record up to 30 or 60 (later 80) minutes; the six channel selector buttons are visible above the transport controls. The only thing to put off a potential purchaser – apart from the relatively short running time – was the steep price tag. However the N1500 was not generally available until the end of 1973; earlier it was only sold to schools and corporate customers, and these customers remained the main purchasers of such an expensive device. The less than 90 minutes maximum recording time would have limited its appeal to wealthy people who weren’t interested in recording long movies, therefore it tended to be only specialist shops and upmarket department stores that stocked the recorder.

The N1500 was replaced by the N1502 in 1976, which was basically an updated N1500 with a more modern case, a digital timer and a few extra features like a ‘Stop motion’ button which froze the picture on-screen. Indeed the N1502 looked almost identical to the forthcoming N1700 which was known to be in development at the time, so the N1502 was probably produced as a stop-gap.

Space oddity…Anyone who walked into the television department of a large upmarket department store (such as Harrods in London) in the 1970s may have been confronted with this space helmet-shaped television known as the Keracolor. This rare model is a design classic, and with 1970s style back in fashion a reconditioned Keracolor retailed in 1998 for as much as £800. Produced in Northwich, Cheshire, there were colour and monochrome versions as well as a smaller portable version, and at least the colour sets used a Decca chassis supported by stickle bricks. (Yes, stickle bricks!) The Keracolor brand was revived much more recently but sadly failed to make a discernible impact on the television world, even minus the stickle bricks.

Send in the clones…the 1970s saw the rise of Japanese manufacturers in Europe and elsewhere, displacing many established companies both in the UK and abroad. Many of the Japanese products from this period were heavily influenced by European models; the JVC Videosphere pictured here being another helmet-based design. The right-hand picture shows the set’s controls – the thumbwheel controls (from left to right) are for brightness, contrast, and off-on/volume, plus rotary VHF and UHF tuning controls. The example shown here is rare since this monochrome TV usually had an orange casing; even so, compared to the Keracolor it is relatively affordable with a 1998 price of £330. Incidentally, the pictures of both this and the Keracolor were taken from BBC Two’s The Antiques Show.

1976 was the year that teletext receivers were sold in UK shops for the very first time, enabling news and information to be displayed on a television screen at a push of a button, but they still weren’t widely available for at least another year. There had been a public teletext service operational since September 1974, but at the start there were only three teletext receivers in existence and they couldn’t be bought in shops, though an electronics magazine published a guide to building your own teletext decoder in 1975 for those who were technically proficient enough to build one from scratch. The Labgear external decoder was the first to be manufactured and sold to the public, with four channels selectable using push buttons on the front panel and a wired remote control used to select pages and other teletext features such as hold and reveal.

CEEFAX had been demonstrated by the BBC to the public as early as a news report on 23 October 1972, but IBA engineers had been independently working on their own ORACLE system therefore it took two years for the two incompatible systems to be reworked into a single standard known as teletext and for broadcasts to commence, with the acronyms CEEFAX and ORACLE being used as the two brand names for the BBC and IBA (ITV) services using the same teletext standard. The falling price of digital electronics made teletext much more affordable during the 1980s and proved to be popular in the UK, remaining in use until it was made obsolete by the analogue TV transmission switch off.

CEEFAX had been demonstrated by the BBC to the public as early as a news report on 23 October 1972, but IBA engineers had been independently working on their own ORACLE system therefore it took two years for the two incompatible systems to be reworked into a single standard known as teletext and for broadcasts to commence, with the acronyms CEEFAX and ORACLE being used as the two brand names for the BBC and IBA (ITV) services using the same teletext standard. The falling price of digital electronics made teletext much more affordable during the 1980s and proved to be popular in the UK, remaining in use until it was made obsolete by the analogue TV transmission switch off.

1977 saw the mass market arrival of a piece of technology that would prove to be very popular for more than 20 years and is still used by many people today, the VCR… (Pictures copyright: Philips Electronics.)

Before the video cassette recorder (VCR) became popular during the 1980s, it was necessary to explain to potential customers exactly what a VCR was and what it could actually do, and those potential customers may not be mechanically-minded either, so the best person to explain what a VCR did in layman’s terms is someone who is recognisably an expert in television but who isn’t necessarily an expert in things mechanical, namely someone like the writer and presenter Denis Norden, therefore Philips were extremely lucky to be able to have Norden present their promotional video demonstrating the benefits of their brand new N1700 VCR. It’s interesting that Philips chose to describe their VCR as simply a “Time Machine” as opposed to a “Television Time Machine” which would have been a much more precise description of what it could do if perhaps a less eye-catching expression.

Before the video cassette recorder (VCR) became popular during the 1980s, it was necessary to explain to potential customers exactly what a VCR was and what it could actually do, and those potential customers may not be mechanically-minded either, so the best person to explain what a VCR did in layman’s terms is someone who is recognisably an expert in television but who isn’t necessarily an expert in things mechanical, namely someone like the writer and presenter Denis Norden, therefore Philips were extremely lucky to be able to have Norden present their promotional video demonstrating the benefits of their brand new N1700 VCR. It’s interesting that Philips chose to describe their VCR as simply a “Time Machine” as opposed to a “Television Time Machine” which would have been a much more precise description of what it could do if perhaps a less eye-catching expression.

The N1700 recorded television broadcasts onto the same size cassette tapes as the N1500, with up to 2 hours of record and play time initially available (Long Play = LP) compared to the 1 hour duration offered by the earlier N1500 series machines (including the N1502 which looked very similar to the N1700); this was achieved by slowing the tape speed down and using improved electronics, therefore recordings were incompatible between VCR-LP and the earlier VCR machines. Even longer tapes were later introduced, enabling 3 hours of recording time on VCR-LP recorders in order to compete with the new VHS and Betamax recorders offered by Japanese manufacturers that were launched in the UK during 1978. (Betamax and VHS had already launched in Japanese/US NTSC markets; 1975 for Betamax and 1976 for VHS respectively, so Philips knew that competition for their product was soon to appear in Europe.)

The N1700 recorded television broadcasts onto the same size cassette tapes as the N1500, with up to 2 hours of record and play time initially available (Long Play = LP) compared to the 1 hour duration offered by the earlier N1500 series machines (including the N1502 which looked very similar to the N1700); this was achieved by slowing the tape speed down and using improved electronics, therefore recordings were incompatible between VCR-LP and the earlier VCR machines. Even longer tapes were later introduced, enabling 3 hours of recording time on VCR-LP recorders in order to compete with the new VHS and Betamax recorders offered by Japanese manufacturers that were launched in the UK during 1978. (Betamax and VHS had already launched in Japanese/US NTSC markets; 1975 for Betamax and 1976 for VHS respectively, so Philips knew that competition for their product was soon to appear in Europe.)

So using the N1700 is as straightforward as: (a) Switching it on; (b) Selecting a TV channel to record from, using the buttons marked 1 to 8; (c) Press the Record and Play buttons down together to start the recording; (d) Press the Stop button to stop the recording. Simple! (The N1500 was nearly as easy to use with perhaps the added complication of setting an audio record level control.)

Just like the earlier N1500/N1502 models, the N1700 VCR recorded television broadcasts onto removable cassette tapes, therefore you had to have inserted a tape into the machine in the first place and ensured that there was enough free space on the tape for a new recording, if necessary rewinding the tape to a suitable point (or the beginning) as shown here, but anyone already familiar with audio cassette recording as most people were at that point during the 1970s would instinctively understand such concepts even if people under the age of 25 nowadays would be even more clueless about VCR’s as the average person would have been in the 1970s. The N1700 did the job it was designed to do on a basic level, but it had no remote control and no picture search facility so you had to make use of a mechanical tape counter and/or the tape compartment window to work out exactly how much tape was left for recording/playback.

Just like the earlier N1500/N1502 models, the N1700 VCR recorded television broadcasts onto removable cassette tapes, therefore you had to have inserted a tape into the machine in the first place and ensured that there was enough free space on the tape for a new recording, if necessary rewinding the tape to a suitable point (or the beginning) as shown here, but anyone already familiar with audio cassette recording as most people were at that point during the 1970s would instinctively understand such concepts even if people under the age of 25 nowadays would be even more clueless about VCR’s as the average person would have been in the 1970s. The N1700 did the job it was designed to do on a basic level, but it had no remote control and no picture search facility so you had to make use of a mechanical tape counter and/or the tape compartment window to work out exactly how much tape was left for recording/playback.

The N1700 did have a basic digital timer capable of recording one programme that had a start time at some point during the next three days, which at least was an improvement over the first Philips VCR N1500 that could only manage a recording start time during the next 24 hours (and was a mechanical timer similar to that used on an old cooker); the N1700 timer was set using a sliding control which was moved one step at a time from left to right, setting the day, start time, and programme duration in that order. Simple and relatively foolproof if not the last word in sophistication, but anything more complex would have made the N1700 too expensive when Philips was trying to keep the overall product cost down.

The N1700 did have a basic digital timer capable of recording one programme that had a start time at some point during the next three days, which at least was an improvement over the first Philips VCR N1500 that could only manage a recording start time during the next 24 hours (and was a mechanical timer similar to that used on an old cooker); the N1700 timer was set using a sliding control which was moved one step at a time from left to right, setting the day, start time, and programme duration in that order. Simple and relatively foolproof if not the last word in sophistication, but anything more complex would have made the N1700 too expensive when Philips was trying to keep the overall product cost down.

If you were really wealthy in the 1970s, you could not only afford a VCR but also have the disposable income to buy an optional camera to plug in the back of it, meaning that you could record home movies on your VCR as long as the lead between camera and VCR was long enough to reach where you wanted to record; fine for recording children playing in the living room or perhaps in the garden from the patio but useless for many other parts of the house or outside. Also the cheap cameras only recorded in black and white, therefore colour recording required additional expense as well as good lighting because the camera tubes weren’t very sensitive to light, so that candlelit dinner party recording may turn out to be a complete washout unless very bright lights were used.

If you were really wealthy in the 1970s, you could not only afford a VCR but also have the disposable income to buy an optional camera to plug in the back of it, meaning that you could record home movies on your VCR as long as the lead between camera and VCR was long enough to reach where you wanted to record; fine for recording children playing in the living room or perhaps in the garden from the patio but useless for many other parts of the house or outside. Also the cheap cameras only recorded in black and white, therefore colour recording required additional expense as well as good lighting because the camera tubes weren’t very sensitive to light, so that candlelit dinner party recording may turn out to be a complete washout unless very bright lights were used.

Denis Norden not only presented the promotion but contributed to its script, being a famous scriptwriter himself having worked alongside Frank Muir amongst others in the past, and this showed in the humourous touches employed including various interactions with his wife (whom you don’t actually see), such as getting ready to go out therefore being able to set the VCR to record something whilst away, etc.; this promotion wasn’t just a factual explanation of how to use a video cassette recorder.

After the practical lesson there were three films intended to be shown in shops for demonstration purposes; skiing, canoeing and land yachting. The skiing film had an accompanying musical soundtrack (Psyche Rock by Pierre Henry) whilst the others featured a natural soundtrack, though there’s another version of the canoeing film with Psyche Rock music also used as a shop demonstration for the N1700.

Grundig produced its own SVR format based on Philips VCR-LP tapes but offering even longer recording times, though it wasn’t popular due to poor availability combined with a near absence of pre-recorded tapes. By 1978 the Japanese-developed Betamax (Sony) and VHS (JVC) videotape formats reached the UK, both offering longer recording times and a wider choice of recorders from different manufacturers compared to Philips’s VCR-LP format. Philips countered by offering a 3 hour tape for the N1700 and the Philips recorder was still the best-selling VCR in 1979 despite the new competition. Philips was also developing a new Video 2000 tape format which unfortunately didn’t reach the market until 1980 when VHS in particular was rapidly becoming established due to greater support from dealers and popularity with schools.

Before the 1980s, schools programmes were almost always watched live as transmitted since there was usually no means of recording them for later use (video recorders only became available to schools from the mid-1960s onwards, were very expensive to purchase and the tapes were pricey as well), so there had to be a delay of at least two minutes before and after each broadcast gave extra time for teachers to file a class of pupils in (and out) of a room that contained a television. In May 1952, the BBC had experimented with schools television via a direct cable link to six schools from Alexandra Palace, but it would be another five years before schools programmes were actually broadcast by the BBC. Under the guidance of Paul Adorian, Associated-Rediffusion commenced the broadcast of schools programmes on 13 May 1957.

Before the 1980s, schools programmes were almost always watched live as transmitted since there was usually no means of recording them for later use (video recorders only became available to schools from the mid-1960s onwards, were very expensive to purchase and the tapes were pricey as well), so there had to be a delay of at least two minutes before and after each broadcast gave extra time for teachers to file a class of pupils in (and out) of a room that contained a television. In May 1952, the BBC had experimented with schools television via a direct cable link to six schools from Alexandra Palace, but it would be another five years before schools programmes were actually broadcast by the BBC. Under the guidance of Paul Adorian, Associated-Rediffusion commenced the broadcast of schools programmes on 13 May 1957. Television sets manufactured before the 1970s made extensive use of valves as opposed to more reliable “solid state” components such as transistors and integrated circuits; these valve-based sets often required adjustment of controls such as brightness and vertical hold before the start of the programme as well as allowing for a period for the TV to have warmed up properly, hence the BBC showing a caption known as a tuning signal for a while before the programme starts which enabled the teacher to make last minute adjustments to the picture settings if required. This Abram Games-designed “angel wings” tuning signal was shown before the start of each days’ broadcast in the 1950s, and continued to be used before schools programmes up until circa 1964, even after its use had been discontinued elsewhere.

Television sets manufactured before the 1970s made extensive use of valves as opposed to more reliable “solid state” components such as transistors and integrated circuits; these valve-based sets often required adjustment of controls such as brightness and vertical hold before the start of the programme as well as allowing for a period for the TV to have warmed up properly, hence the BBC showing a caption known as a tuning signal for a while before the programme starts which enabled the teacher to make last minute adjustments to the picture settings if required. This Abram Games-designed “angel wings” tuning signal was shown before the start of each days’ broadcast in the 1950s, and continued to be used before schools programmes up until circa 1964, even after its use had been discontinued elsewhere. The first transmitted BBC programme for schools (Geography) was broadcast on 24 September 1957 from the Lime Grove studios, with only one schools programme shown each afternoon during term time to begin with, and all the initial programmes such as Living In The Commonwealth and Science and Life were predominantly aimed at older children. A short 5 second filmed ident sequence with orchestral accompaniment was used to introduce BBC Television For Schools (as it was called), and we can perhaps assume that this film was used as an opening sequence for schools programmes until the summer term of 1960; it had certainly been dropped by 1962 when the “Schools Opening Film” was 1 minute long in duration.

The first transmitted BBC programme for schools (Geography) was broadcast on 24 September 1957 from the Lime Grove studios, with only one schools programme shown each afternoon during term time to begin with, and all the initial programmes such as Living In The Commonwealth and Science and Life were predominantly aimed at older children. A short 5 second filmed ident sequence with orchestral accompaniment was used to introduce BBC Television For Schools (as it was called), and we can perhaps assume that this film was used as an opening sequence for schools programmes until the summer term of 1960; it had certainly been dropped by 1962 when the “Schools Opening Film” was 1 minute long in duration. During the last second of the ident sequence, the torch (and the caption) momentarily flickered brighter before the continuity announcer appeared on-screen to formally introduce the programme; something that may also relate to the flashes of light used for the “bat’s wings” logo from the same period. (Indeed, elements of the “bat’s wings” design with flashes of light could be seen being used in schools continuity until October 1961; a year after it was discontinued elsewhere.) Even by 1950s standards, this style of on-screen presentation was surprisingly old-fashioned but presumably a traditional look was adopted in order to appeal to teachers that were reluctant to embrace modern technology in the classroom. However despite an initial lack of programming, schools quickly warmed to the idea of television as a teaching medium and they were eagerly buying televisions to such an extent that they had to be restrained from excessively doing so.

During the last second of the ident sequence, the torch (and the caption) momentarily flickered brighter before the continuity announcer appeared on-screen to formally introduce the programme; something that may also relate to the flashes of light used for the “bat’s wings” logo from the same period. (Indeed, elements of the “bat’s wings” design with flashes of light could be seen being used in schools continuity until October 1961; a year after it was discontinued elsewhere.) Even by 1950s standards, this style of on-screen presentation was surprisingly old-fashioned but presumably a traditional look was adopted in order to appeal to teachers that were reluctant to embrace modern technology in the classroom. However despite an initial lack of programming, schools quickly warmed to the idea of television as a teaching medium and they were eagerly buying televisions to such an extent that they had to be restrained from excessively doing so. A promotional film This is the BBC gives us a brief insight into the production of schools programmes during the late 1950s; the continuity announcer pictured here is introducing Programme 3 of the series Transport and Communication. The BBC actually referred to schools broadcasts in period literature as being “Broadcasts To Schools”.

A promotional film This is the BBC gives us a brief insight into the production of schools programmes during the late 1950s; the continuity announcer pictured here is introducing Programme 3 of the series Transport and Communication. The BBC actually referred to schools broadcasts in period literature as being “Broadcasts To Schools”. Programme 3 of the aforementioned Transport and Communication series was all about the history of the motor car, so an example of the very first mass produced car – the Model T Ford – was placed in the studio. The presenter was Arthur Garratt (pictured here next to the car).

Programme 3 of the aforementioned Transport and Communication series was all about the history of the motor car, so an example of the very first mass produced car – the Model T Ford – was placed in the studio. The presenter was Arthur Garratt (pictured here next to the car). The tuning signal caption shown here is likely to have been first used as early as Autumn Term 1960 (when a morning schools programme was introduced); it was used before the start of each schools programme and consisted of a circle divided into five segments of black, white and three shades of grey in the style of a pie chart on a pale grey background, hence the term “BBC Schools Pie Chart”. From (at least) 1964 to 1967 there was a countdown sequence used before the start of the programme which had the pie chart slowly disappear; the circular chart was divided into small segments, with each segment of the pie chart being replaced by the corresponding segment of a plain clock face (identical to the clock face below minus the second hand) starting from the top, one for each second in a clockwise direction. A piece of music written by Lionel Salter entitled “We are almost ready to begin” was used to accompany the animation from 1964 onwards, and the tune’s duration was 1 minute 55 seconds, with 5 seconds’ silence for the announcement ID. (The first pie chart was also branded ‘BBC tv’ unlike the BBC branding shown here that was used from 1967 onwards.)

The tuning signal caption shown here is likely to have been first used as early as Autumn Term 1960 (when a morning schools programme was introduced); it was used before the start of each schools programme and consisted of a circle divided into five segments of black, white and three shades of grey in the style of a pie chart on a pale grey background, hence the term “BBC Schools Pie Chart”. From (at least) 1964 to 1967 there was a countdown sequence used before the start of the programme which had the pie chart slowly disappear; the circular chart was divided into small segments, with each segment of the pie chart being replaced by the corresponding segment of a plain clock face (identical to the clock face below minus the second hand) starting from the top, one for each second in a clockwise direction. A piece of music written by Lionel Salter entitled “We are almost ready to begin” was used to accompany the animation from 1964 onwards, and the tune’s duration was 1 minute 55 seconds, with 5 seconds’ silence for the announcement ID. (The first pie chart was also branded ‘BBC tv’ unlike the BBC branding shown here that was used from 1967 onwards.) From 1967 until (at least) November 1974, the ‘vanishing segments’ animation used for the final minute was replaced by this simple clock face with a single continuously moving second hand, though the pie chart itself was still being shown prior to the final minute countdown to the programme start; the accompanying music now being used was usually a percussive piece known as “Guadalajara” that was written by Leonard Salzedo (who also wrote the Open University theme that was the first few bars of a longer piece). Broadcast quality copies (albeit recorded on film) of this pie chart and clock sequence exist before the start of some BBC Northern Ireland schools programmes because an ident was sometimes recorded alongside the programme.

From 1967 until (at least) November 1974, the ‘vanishing segments’ animation used for the final minute was replaced by this simple clock face with a single continuously moving second hand, though the pie chart itself was still being shown prior to the final minute countdown to the programme start; the accompanying music now being used was usually a percussive piece known as “Guadalajara” that was written by Leonard Salzedo (who also wrote the Open University theme that was the first few bars of a longer piece). Broadcast quality copies (albeit recorded on film) of this pie chart and clock sequence exist before the start of some BBC Northern Ireland schools programmes because an ident was sometimes recorded alongside the programme. Occasionally an “Announcement For Teachers” may have been read during the final minute whilst the clock hand was steadily moving around the face to the 12 o’clock position when the programme starts, with this caption being overlaid on the clock, but more commonly such announcements were made at other times when this caption on its own would have been displayed. (The same caption was also used later in the 1970s for announcements.)

Occasionally an “Announcement For Teachers” may have been read during the final minute whilst the clock hand was steadily moving around the face to the 12 o’clock position when the programme starts, with this caption being overlaid on the clock, but more commonly such announcements were made at other times when this caption on its own would have been displayed. (The same caption was also used later in the 1970s for announcements.) Then of course there were the programmes themselves – BBC Schools programming caters for a wide range of subjects and abilities, with series such as Maths Today and Maths Workshop (for older children); the latter being shown well into the 1970s despite being made in black and white. Programmes were often repeated for the benefit of teachers so that they could try and incorporate them into the school timetable which was often difficult since many schools had no form of video recording at that time.

Then of course there were the programmes themselves – BBC Schools programming caters for a wide range of subjects and abilities, with series such as Maths Today and Maths Workshop (for older children); the latter being shown well into the 1970s despite being made in black and white. Programmes were often repeated for the benefit of teachers so that they could try and incorporate them into the school timetable which was often difficult since many schools had no form of video recording at that time. Here is an example of a BBC Schools sex education programme from the late 1960s that would inevitably provide a useful classroom resource triggering a discussion about the facts of life, with television being able to provide a far more powerful illustrative medium compared to books or blackboard drawings for this particular topic.

Here is an example of a BBC Schools sex education programme from the late 1960s that would inevitably provide a useful classroom resource triggering a discussion about the facts of life, with television being able to provide a far more powerful illustrative medium compared to books or blackboard drawings for this particular topic. Very occasionally the pie chart tuning signal itself would feature as part of an engineering test startup sequence if such a test was scheduled for a weekday morning during term time, in which case the pie chart tuning signal would appear on screen then very slowly fade away over the course of a minute to leave a black screen before appearing again shortly before the start of the first programme. The sequence would also feature a greyscale (sawtooth) tuning pattern with tone.

Very occasionally the pie chart tuning signal itself would feature as part of an engineering test startup sequence if such a test was scheduled for a weekday morning during term time, in which case the pie chart tuning signal would appear on screen then very slowly fade away over the course of a minute to leave a black screen before appearing again shortly before the start of the first programme. The sequence would also feature a greyscale (sawtooth) tuning pattern with tone. With more and more schools programmes being made in colour as well as more and more schools acquiring colour TV’s – though there were still a significant number of primary schools in particular that had only black and white televisions even at the end of the 1970s – the pie chart’s days were obviously numbered, therefore something more contemporary was devised for schools programme presentation.

With more and more schools programmes being made in colour as well as more and more schools acquiring colour TV’s – though there were still a significant number of primary schools in particular that had only black and white televisions even at the end of the 1970s – the pie chart’s days were obviously numbered, therefore something more contemporary was devised for schools programme presentation.

Examples of BBC Schools programmes shown during the 1970s include A Good Read, A Job Worth Doing?, Going To Work, Maths Topics, Mathshow, Merry-go-round for primary school children, Scene, Swim, and Watch. Some of these programmes continued to be produced or shown for years after the 1970s but the introduction of GCSE qualifications (replacing ‘O’ levels, with the first GCSE exams in the Summer of 1988) made some of these old programmes redundant.

Examples of BBC Schools programmes shown during the 1970s include A Good Read, A Job Worth Doing?, Going To Work, Maths Topics, Mathshow, Merry-go-round for primary school children, Scene, Swim, and Watch. Some of these programmes continued to be produced or shown for years after the 1970s but the introduction of GCSE qualifications (replacing ‘O’ levels, with the first GCSE exams in the Summer of 1988) made some of these old programmes redundant.

From 1977 onwards until the Summer Term of 1983 a “dots clock” was used as a replacement for the diamond animation before schools programmes, with a full circle of dots shown when the clock first appears. When watching the dots disappear one by one clockwise each second as the clock counts down to the start of the programme, you may notice that the dots don’t instantly disappear but seem to shrink as they vanish due to the mechanical nature of the clock. Various pieces of music were used to accompany the clock, including Cat Stevens’ Remember the days of the old schoolyard, a medley of ABBA songs and a rather memorable cover version of the original Star Wars theme. Originally the Schools and Colleges logo in the centre of the clock rotated every so often but it’s very likely that the turning mechanism broke down early on because the logo became static at some point not too long after the clock was first used.

From 1977 onwards until the Summer Term of 1983 a “dots clock” was used as a replacement for the diamond animation before schools programmes, with a full circle of dots shown when the clock first appears. When watching the dots disappear one by one clockwise each second as the clock counts down to the start of the programme, you may notice that the dots don’t instantly disappear but seem to shrink as they vanish due to the mechanical nature of the clock. Various pieces of music were used to accompany the clock, including Cat Stevens’ Remember the days of the old schoolyard, a medley of ABBA songs and a rather memorable cover version of the original Star Wars theme. Originally the Schools and Colleges logo in the centre of the clock rotated every so often but it’s very likely that the turning mechanism broke down early on because the logo became static at some point not too long after the clock was first used. Autumn Term 1983 saw schools programmes permanently move to BBC2 and the use of a dots clock was abandoned at this point in favour of a more conventional “Daytime on 2” style of continuity, though the “Coming Shortly…” method of filling short gaps in the schedule continued for a while longer as well as a 15 second digital countdown timer being adopted later on in the decade. More and more schools now had video recorders so could easily record programmes and play them back at times to suit the lessons as opposed to timing the lessons to fit in with the television programmes.

Autumn Term 1983 saw schools programmes permanently move to BBC2 and the use of a dots clock was abandoned at this point in favour of a more conventional “Daytime on 2” style of continuity, though the “Coming Shortly…” method of filling short gaps in the schedule continued for a while longer as well as a 15 second digital countdown timer being adopted later on in the decade. More and more schools now had video recorders so could easily record programmes and play them back at times to suit the lessons as opposed to timing the lessons to fit in with the television programmes. Prior to the 1960s, this is how a few people had their first view of ‘colour’ television – in the 1950s you could buy a ‘colourising’ filter, place it over your existing black and white screen, and let your imagination do the rest… John Logie Baird, the pioneer of television, was working on stereoscopic colour television shortly before his death in 1946, and the Americans were conducting experiments. But the technology was very complex; the problem was how to transmit colour information alongside an existing black and white image, therefore maintaining ‘backwards’ compatibility with existing receivers.

Prior to the 1960s, this is how a few people had their first view of ‘colour’ television – in the 1950s you could buy a ‘colourising’ filter, place it over your existing black and white screen, and let your imagination do the rest… John Logie Baird, the pioneer of television, was working on stereoscopic colour television shortly before his death in 1946, and the Americans were conducting experiments. But the technology was very complex; the problem was how to transmit colour information alongside an existing black and white image, therefore maintaining ‘backwards’ compatibility with existing receivers. From 10 October 1955 the BBC experimented with colour television, firstly with a 405 line version of the American NTSC system – the first generally available electronic-based system of colour transmission designed for backwards compatability with existing monochrome transmissions. Low power test transmissions were from Alexandra Palace (one of the original studios being re-equipped for the purpose), using specially made receivers, but to start a public 405-line colour service at this stage would result in Britain having to commit long term to the pre-war 405-line standard which was out of step with continental Europe (which used the superior post-war 625 line system).

From 10 October 1955 the BBC experimented with colour television, firstly with a 405 line version of the American NTSC system – the first generally available electronic-based system of colour transmission designed for backwards compatability with existing monochrome transmissions. Low power test transmissions were from Alexandra Palace (one of the original studios being re-equipped for the purpose), using specially made receivers, but to start a public 405-line colour service at this stage would result in Britain having to commit long term to the pre-war 405-line standard which was out of step with continental Europe (which used the superior post-war 625 line system).

The song used in this particular test broadcast was “Early one morning”, and the participants had to wear different makeup compared with that used for monochrome broadcasts as well as brightly-coloured costumes featuring different colours.

The song used in this particular test broadcast was “Early one morning”, and the participants had to wear different makeup compared with that used for monochrome broadcasts as well as brightly-coloured costumes featuring different colours. A major problem with early colour television equipment was its unreliability combined with the huge number of adjustments that were required for a good quality picture. The colour television receivers used for the BBC tests were individually handbuilt by companies such as Bush and Philips, with various specialist components such as colour television tubes having to be sourced from America; the sets themselves were designed to be easily maintainable by engineers despite their huge complexity, which was particularly true of the receivers constructed for the later PAL tests.

A major problem with early colour television equipment was its unreliability combined with the huge number of adjustments that were required for a good quality picture. The colour television receivers used for the BBC tests were individually handbuilt by companies such as Bush and Philips, with various specialist components such as colour television tubes having to be sourced from America; the sets themselves were designed to be easily maintainable by engineers despite their huge complexity, which was particularly true of the receivers constructed for the later PAL tests. Later the French developed SECAM (Sequential Colour with Memory), and Telefunken in Germany developed PAL (Phase Alternate Line) which represented two differing approaches of solving the colour problems encountered with NTSC, and the BBC experimented using both, though there were other problems to be solved. The insensitivity and inaccuracy of early colour tv cameras and its associated circuitry meant that without adjustments the resulting picture either had a colour cast and/or made flesh tones look too red, so extra studio lighting and make-up was required. In 1961 a committee meeting in Stockholm allocated UHF frequencies for 36 European countries, enabling the Government to plan ahead.

Later the French developed SECAM (Sequential Colour with Memory), and Telefunken in Germany developed PAL (Phase Alternate Line) which represented two differing approaches of solving the colour problems encountered with NTSC, and the BBC experimented using both, though there were other problems to be solved. The insensitivity and inaccuracy of early colour tv cameras and its associated circuitry meant that without adjustments the resulting picture either had a colour cast and/or made flesh tones look too red, so extra studio lighting and make-up was required. In 1961 a committee meeting in Stockholm allocated UHF frequencies for 36 European countries, enabling the Government to plan ahead. After much deliberation, the government chose the PAL system – which although was more complex (hence expensive) it gave the best results. Most of Europe also chose PAL, and BBC2 started its UHF 625-line colour service on 1 July 1967 with Wimbledon tennis coverage (there were a few earlier test transmissions), though initially only a few programmes in the schedule were actually in colour. BBC2’s first colour ident was simply the standard ‘2’ logo electronically-tinted pale blue.

After much deliberation, the government chose the PAL system – which although was more complex (hence expensive) it gave the best results. Most of Europe also chose PAL, and BBC2 started its UHF 625-line colour service on 1 July 1967 with Wimbledon tennis coverage (there were a few earlier test transmissions), though initially only a few programmes in the schedule were actually in colour. BBC2’s first colour ident was simply the standard ‘2’ logo electronically-tinted pale blue.

By December 1967 colour was available in London, the Midlands, the North and South of England. Other early colour programmes included The World About Us (which basically used stock colour documentary footage – the first programme featured volcanoes), Almost Human (about domesticated animals) and International Cabaret. The BBC-produced 1968 Eurovision Song Contest was shown live in black-and-white on BBC1 and in colour in West Germany but repeated the next day in colour on BBC2.

By December 1967 colour was available in London, the Midlands, the North and South of England. Other early colour programmes included The World About Us (which basically used stock colour documentary footage – the first programme featured volcanoes), Almost Human (about domesticated animals) and International Cabaret. The BBC-produced 1968 Eurovision Song Contest was shown live in black-and-white on BBC1 and in colour in West Germany but repeated the next day in colour on BBC2. There were many more manufacturers of television receivers in the 1960s than there are today; Sobell, MacMichael, GEC, Ekco, HMV, ITT, and Ferguson were just a few of the more notable ones, though later on more obscure models were imported to meet increasing demand. Early colour television sets used valves and were very bulky, expensive, unreliable, some had poor colour quality, and some sets were prone to overheating. After a succession of house fires people were advised to stay in the same room as their television for one hour after it was switched off.

There were many more manufacturers of television receivers in the 1960s than there are today; Sobell, MacMichael, GEC, Ekco, HMV, ITT, and Ferguson were just a few of the more notable ones, though later on more obscure models were imported to meet increasing demand. Early colour television sets used valves and were very bulky, expensive, unreliable, some had poor colour quality, and some sets were prone to overheating. After a succession of house fires people were advised to stay in the same room as their television for one hour after it was switched off. The HMV Colourmaster was a colour television featuring a genuine world-first: an all-transistor chassis with no valves apart from the cathode ray tube which technically speaking is a valve in itself; a design practice that was soon to be universally adopted. Despite a lack of valves, the Colourmaster was still a very bulky television due to the complexity of the transistor circuitry and the sheer bulk of the colour display tube. Available in 19″ and 25″ sizes, the price of the 25″ Colourmaster was an eye-watering £362.18s (pre-decimal) in 1968, so it’s no wonder that colour televisions were usually rented as opposed to purchased outright. (By comparison you could buy a very decent black and white television for a quarter of the price.)

The HMV Colourmaster was a colour television featuring a genuine world-first: an all-transistor chassis with no valves apart from the cathode ray tube which technically speaking is a valve in itself; a design practice that was soon to be universally adopted. Despite a lack of valves, the Colourmaster was still a very bulky television due to the complexity of the transistor circuitry and the sheer bulk of the colour display tube. Available in 19″ and 25″ sizes, the price of the 25″ Colourmaster was an eye-watering £362.18s (pre-decimal) in 1968, so it’s no wonder that colour televisions were usually rented as opposed to purchased outright. (By comparison you could buy a very decent black and white television for a quarter of the price.) By 1968 many ITV franchises realised that they too had to prepare themselves for a future colour service. The first to do so was TWW, followed closely by ABC: ironically both were to lose their franchise the same year (though ABC joined up with Rediffusion to form Thames). TWW’s first (and hence ITV’s first) colour camera production (pictured) was Colour One – it was directed by Mike Towers (later Managing Director of HTV) and was done purely for internal demonstration purposes. No recording exists because there was nothing available to record it with.

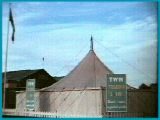

By 1968 many ITV franchises realised that they too had to prepare themselves for a future colour service. The first to do so was TWW, followed closely by ABC: ironically both were to lose their franchise the same year (though ABC joined up with Rediffusion to form Thames). TWW’s first (and hence ITV’s first) colour camera production (pictured) was Colour One – it was directed by Mike Towers (later Managing Director of HTV) and was done purely for internal demonstration purposes. No recording exists because there was nothing available to record it with. TWW also took out their colour cameras (EMI type 204 Vidicon using mirror optical splitting and a turret of wide angle adaptors, originally made for medical applications) for publicity demonstrations – pictured is the TWW tent at a Welsh Eisteddfod. The colour equipment used was a work of ingenuity – only a single RGB monitor was available and the only colour encoder available was a NTSC encoder, so it had to be modified to provide a PAL output which was no easy task.

TWW also took out their colour cameras (EMI type 204 Vidicon using mirror optical splitting and a turret of wide angle adaptors, originally made for medical applications) for publicity demonstrations – pictured is the TWW tent at a Welsh Eisteddfod. The colour equipment used was a work of ingenuity – only a single RGB monitor was available and the only colour encoder available was a NTSC encoder, so it had to be modified to provide a PAL output which was no easy task.

During the early 1970s much of England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland were still totally without colour television, and despite a mini-budget in July 1971 boosting sales, by 1972 only 17% of households had colour television receivers though the Olympic Games in that year did help to stimulate interest. However tales of overheating and unreliability still put off many potential purchasers and the cost was still prohibitive for some, though TV rental provided an affordable alternative to outright purchase.

During the early 1970s much of England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland were still totally without colour television, and despite a mini-budget in July 1971 boosting sales, by 1972 only 17% of households had colour television receivers though the Olympic Games in that year did help to stimulate interest. However tales of overheating and unreliability still put off many potential purchasers and the cost was still prohibitive for some, though TV rental provided an affordable alternative to outright purchase. By 1976 colour television sets were smaller, far more reliable and they no longer caught fire due to their ‘solid-state’ design, meaning that no valves are used apart from the picture tube. Portable colour televisions became available, though most of these were still tied to the mains supply due to their high power consumption; the exceptions usually had 10 inch or smaller screens. Picture quality became vastly improved, and the falling price of sets meant that the number of colour televisions had rapidly increased to over 7.5 million by 1976. The Home Entertainment Show 1976 in London showcased recent innovations such as teletext, and colour transmissions finally reached the Channel Islands in the same year (it took a long time due to the technical difficulties in providing a UHF link to England).

By 1976 colour television sets were smaller, far more reliable and they no longer caught fire due to their ‘solid-state’ design, meaning that no valves are used apart from the picture tube. Portable colour televisions became available, though most of these were still tied to the mains supply due to their high power consumption; the exceptions usually had 10 inch or smaller screens. Picture quality became vastly improved, and the falling price of sets meant that the number of colour televisions had rapidly increased to over 7.5 million by 1976. The Home Entertainment Show 1976 in London showcased recent innovations such as teletext, and colour transmissions finally reached the Channel Islands in the same year (it took a long time due to the technical difficulties in providing a UHF link to England). By the end of the 1970s manufacturers were looking to add more features to their televisions, and the advent of reasonably priced silicon chip circuitry meant that special features such as teletext could be added (a free information service whereby information is transmitted as ‘pages’) as well as sometimes other short-lived features such as ‘viewdata’ (a primitive internet-style service using crude block graphics as well as text) and bat-and-ball style video games. Teletext was the only special feature that became popular because it was cheap to add and free to use, together with remote control operation and electronic tuning. Early wireless remote controls mainly used ultrasound waves which were inaudible to humans but could make dogs bark.

By the end of the 1970s manufacturers were looking to add more features to their televisions, and the advent of reasonably priced silicon chip circuitry meant that special features such as teletext could be added (a free information service whereby information is transmitted as ‘pages’) as well as sometimes other short-lived features such as ‘viewdata’ (a primitive internet-style service using crude block graphics as well as text) and bat-and-ball style video games. Teletext was the only special feature that became popular because it was cheap to add and free to use, together with remote control operation and electronic tuning. Early wireless remote controls mainly used ultrasound waves which were inaudible to humans but could make dogs bark. The 1980s and 1990s saw further developments in television design and technology. As early as the mid 1970s the German set maker Grundig had introduced a system using easily changeable internal modules with diagnostic lights so the set could even tell the engineer which part needed replacing. This idea never caught on but the basic concept of making the set simpler and cheaper to make remained. In 1983 Ferguson introduced the TX100 chassis, with some impressive claims (23% fewer adjustments, 5% fewer components, etc.), and new technologies continued to add features and reduce costs. NICAM stereo sound was introduced at the end of the 1980s, and television has continued to evolve since then with digital widescreen broadcasting commencing in 1998, high definition (HD) broadcasts beginning in the UK in 2006, and ultra high definition (UHD, or 4K) broadcasting is now a reality; experiments using this technology having taken place from 2012 onwards. Even higher resolutions are currently being considered though another brief flirtation with 3D television seems to have ended, at least for the time being.

The 1980s and 1990s saw further developments in television design and technology. As early as the mid 1970s the German set maker Grundig had introduced a system using easily changeable internal modules with diagnostic lights so the set could even tell the engineer which part needed replacing. This idea never caught on but the basic concept of making the set simpler and cheaper to make remained. In 1983 Ferguson introduced the TX100 chassis, with some impressive claims (23% fewer adjustments, 5% fewer components, etc.), and new technologies continued to add features and reduce costs. NICAM stereo sound was introduced at the end of the 1980s, and television has continued to evolve since then with digital widescreen broadcasting commencing in 1998, high definition (HD) broadcasts beginning in the UK in 2006, and ultra high definition (UHD, or 4K) broadcasting is now a reality; experiments using this technology having taken place from 2012 onwards. Even higher resolutions are currently being considered though another brief flirtation with 3D television seems to have ended, at least for the time being. John Logie Baird is often credited with the invention of television, though in reality it was the culmination of various independent discoveries. However Baird was responsible for bringing various elements together and promoting the idea of television commercially to such an extent that it became a reality.

John Logie Baird is often credited with the invention of television, though in reality it was the culmination of various independent discoveries. However Baird was responsible for bringing various elements together and promoting the idea of television commercially to such an extent that it became a reality. Baird, although a Scot, had lived in London for much of his life. And he had also suffered from ill health for most of his life as well, so on the advice of his doctor he moved to the South Coast of England to live in the seaside resort of Hastings. Against medical advice, he carried on developing his ideas for various inventions both large and small, including the one that interested him the most – television.

Baird, although a Scot, had lived in London for much of his life. And he had also suffered from ill health for most of his life as well, so on the advice of his doctor he moved to the South Coast of England to live in the seaside resort of Hastings. Against medical advice, he carried on developing his ideas for various inventions both large and small, including the one that interested him the most – television. Lynton Crescent was to be the place where Baird managed to finally realise his dream; that of the transmission of an image without the use of wires or any form of trickery. He had been following the various attempts made by other people to transmit pictures with great interest, and very soon he was to attempt to do the same as well.

Lynton Crescent was to be the place where Baird managed to finally realise his dream; that of the transmission of an image without the use of wires or any form of trickery. He had been following the various attempts made by other people to transmit pictures with great interest, and very soon he was to attempt to do the same as well. He built his pioneering equipment using what odds and ends he could lay his hands on, such as an old tea chest, an old bicycle lamp, cardboard from a hat box, an old biscuit tin, darning needles, string and tallow wax. With this he managed to construct a mechanical scanning system for the transmission and reception of images – he received help from local people in order to fund the experiment.

He built his pioneering equipment using what odds and ends he could lay his hands on, such as an old tea chest, an old bicycle lamp, cardboard from a hat box, an old biscuit tin, darning needles, string and tallow wax. With this he managed to construct a mechanical scanning system for the transmission and reception of images – he received help from local people in order to fund the experiment. By the end of 1923 John Logie Baird, through sheer determination had finally managed to build what was effectively the world’s first complete television transmitter and receiver. Its achievements may today look relatively modest but by the standards of the day it was a technical miracle – the speed of both the transmitter and receiver had to be perfectly synchronised in tandem for an image to be viewable.

By the end of 1923 John Logie Baird, through sheer determination had finally managed to build what was effectively the world’s first complete television transmitter and receiver. Its achievements may today look relatively modest but by the standards of the day it was a technical miracle – the speed of both the transmitter and receiver had to be perfectly synchronised in tandem for an image to be viewable. The very first transmitted image was that of a simple cross made of cardboard (visible on the right hand side of the picture); the camera and transmitter were a few feet away on the other side of the room. In January 1924 the Daily News reported on this feat, and public interest rapidly grew as a result of this successful experiment. Mr. Twigg the landlord was rather less impressed though – since Baird had electrocuted himself twice and caused a small explosion, he evicted Baird from his lodgings. The first chapter of television history had effectively drawn to a close.

The very first transmitted image was that of a simple cross made of cardboard (visible on the right hand side of the picture); the camera and transmitter were a few feet away on the other side of the room. In January 1924 the Daily News reported on this feat, and public interest rapidly grew as a result of this successful experiment. Mr. Twigg the landlord was rather less impressed though – since Baird had electrocuted himself twice and caused a small explosion, he evicted Baird from his lodgings. The first chapter of television history had effectively drawn to a close. Up to 1964 there were only two television channels in the UK: BBC and ITV, though if you lived on the boundary of two ITV areas it was possible to receive more than one ITV service, but the majority of the programmes would essentially be the same. BBC2, it was hoped, would offer more than just ‘more of the same’ and would have an entirely different ‘character’ to the other two established networks. BBC2 would also be different in that it was transmitted using 625 lines on UHF channels which matched the post-war standard ratified by convention and used in continental Europe as opposed to the existing 405 line pre-war UK system, though colour was still a few years away and its introduction was delayed by the move to 625 lines.

Up to 1964 there were only two television channels in the UK: BBC and ITV, though if you lived on the boundary of two ITV areas it was possible to receive more than one ITV service, but the majority of the programmes would essentially be the same. BBC2, it was hoped, would offer more than just ‘more of the same’ and would have an entirely different ‘character’ to the other two established networks. BBC2 would also be different in that it was transmitted using 625 lines on UHF channels which matched the post-war standard ratified by convention and used in continental Europe as opposed to the existing 405 line pre-war UK system, though colour was still a few years away and its introduction was delayed by the move to 625 lines. From the start, BBC2 faced an uphill struggle. Because of the different line and frequency standards used for BBC2, a new television was required along with an additional aerial in order to receive the new service. The early sets that could receive BBC2 were known as dual standard receivers because they had to cater for BBC1 and ITV on 405 lines VHF as well; it would be a few years (dependent on the area) for BBC1 and ITV to also be made available on UHF, with the last area to switch to UHF being the Channel Islands in 1976. A few 405 line VHF sets were capable of being upgraded to 625 line UHF operation.

From the start, BBC2 faced an uphill struggle. Because of the different line and frequency standards used for BBC2, a new television was required along with an additional aerial in order to receive the new service. The early sets that could receive BBC2 were known as dual standard receivers because they had to cater for BBC1 and ITV on 405 lines VHF as well; it would be a few years (dependent on the area) for BBC1 and ITV to also be made available on UHF, with the last area to switch to UHF being the Channel Islands in 1976. A few 405 line VHF sets were capable of being upgraded to 625 line UHF operation. BBC2’s opening night was a total disaster; it was hit by a major power failure, though the fireworks which featured the two kangaroos (the baby one jumping out of its mother’s pouch) still managed to shine on the opening night. These kangaroo mascots (Hullaballoo and Custard) were initially used to publicise the new service, with the basic concept being that BBC2 was the new ‘child’ of BBC-tv (which was soon to be known as BBC1 – though because BBC2 was only viewable in London and the Midlands to begin with, the idea was slow to catch on).

BBC2’s opening night was a total disaster; it was hit by a major power failure, though the fireworks which featured the two kangaroos (the baby one jumping out of its mother’s pouch) still managed to shine on the opening night. These kangaroo mascots (Hullaballoo and Custard) were initially used to publicise the new service, with the basic concept being that BBC2 was the new ‘child’ of BBC-tv (which was soon to be known as BBC1 – though because BBC2 was only viewable in London and the Midlands to begin with, the idea was slow to catch on). The previous day’s blackout meant that the first programme to be transmitted in its entirety was Play School the following morning, though the channel then closed down until the early evening. Play School became a very popular series for pre-school children and was produced right up until 1988 when it was replaced by Playdays, and elements of Play School were also used in Tikkabilla.

The previous day’s blackout meant that the first programme to be transmitted in its entirety was Play School the following morning, though the channel then closed down until the early evening. Play School became a very popular series for pre-school children and was produced right up until 1988 when it was replaced by Playdays, and elements of Play School were also used in Tikkabilla. This picture was taken from the ‘proper’ start of the first early evening programmes, with the candle being symbolic of the previous evening’s power failure. Also because not everybody could receive the new service, most BBC2 programmes had to be repeated later on BBC1 after their first showing. Each evening initially started with a 10 minute programme presented by Denis Twohy (pictured), entitled

This picture was taken from the ‘proper’ start of the first early evening programmes, with the candle being symbolic of the previous evening’s power failure. Also because not everybody could receive the new service, most BBC2 programmes had to be repeated later on BBC1 after their first showing. Each evening initially started with a 10 minute programme presented by Denis Twohy (pictured), entitled  Despite all of this, and a slow start not helped by the channel’s early ‘Seven Faces’ schedule (each day was dedicated to a particular theme such as education on Tuesdays) which was unpopular and soon scrapped, BBC2 built up a loyal audience, courtesy of its quality programming which often catered for more specialist tastes.

Despite all of this, and a slow start not helped by the channel’s early ‘Seven Faces’ schedule (each day was dedicated to a particular theme such as education on Tuesdays) which was unpopular and soon scrapped, BBC2 built up a loyal audience, courtesy of its quality programming which often catered for more specialist tastes. What were known as Trade Test Colour Films were first transmitted on BBC2 in 1964 during the weeks before the channel launched, then they were shown sporadically prior to a regular schedule commencing on 21 August 1967 ahead of the formal introduction of a colour service on BBC2. A wide variety of short colour films (usually less than 30 minutes in duration) were shown at various times of the day when no scheduled programmes were being broadcast, such as

What were known as Trade Test Colour Films were first transmitted on BBC2 in 1964 during the weeks before the channel launched, then they were shown sporadically prior to a regular schedule commencing on 21 August 1967 ahead of the formal introduction of a colour service on BBC2. A wide variety of short colour films (usually less than 30 minutes in duration) were shown at various times of the day when no scheduled programmes were being broadcast, such as  Top class documentaries such as Civilisation and The Ascent of Man helped give BBC2 (and the BBC in general) an enviable reputation that still exists to this day. Rightly or wrongly BBC2 initially had a reputation for being a ‘highbrow’ channel, and David Attenborough who was the channel’s controller from 1965-69 was broadly responsible for creating this upmarket image as an alternative to BBC1 and ITV.

Top class documentaries such as Civilisation and The Ascent of Man helped give BBC2 (and the BBC in general) an enviable reputation that still exists to this day. Rightly or wrongly BBC2 initially had a reputation for being a ‘highbrow’ channel, and David Attenborough who was the channel’s controller from 1965-69 was broadly responsible for creating this upmarket image as an alternative to BBC1 and ITV. And it wasn’t just the documentaries that gave BBC2 a highbrow image; early music offerings included classical concerts and opera as well as jazz in the famous Jazz 625 series, but BBC2 also let its hair down with popular music: Colour Me Pop ran from 1968-9 as a spinoff from Late Night Line-Up and featured one artist per programme. Unfortunately very little survives of Colour Me Pop in the BBC’s archive unlike its spiritual successor The Old Grey Whistle Test, which began in 1972 and was presented by Bob Harris.