Over the years there have been many varieties of quiz show, from the intellectual (such as Call My Bluff) to the unashamedly populist Play Your Cards Right. QD: The Master Game was fundamentally similar to shows such as the mid-1980s TVS-produced Ultra Quiz, though it also had an affinity with the more intellectual shows. To briefly summarise – over five half-hour programmes (shown Monday to Friday on Channel 4 in 1991) an initially large number of contestants take part in a series of intellectual challenges; the number of contestants are reduced through elimination to a more manageable number for the final stages.

Over the years there have been many varieties of quiz show, from the intellectual (such as Call My Bluff) to the unashamedly populist Play Your Cards Right. QD: The Master Game was fundamentally similar to shows such as the mid-1980s TVS-produced Ultra Quiz, though it also had an affinity with the more intellectual shows. To briefly summarise – over five half-hour programmes (shown Monday to Friday on Channel 4 in 1991) an initially large number of contestants take part in a series of intellectual challenges; the number of contestants are reduced through elimination to a more manageable number for the final stages.

So what exactly did QD stand for, apart from yet another quiz game? An ongoing competition that took place during the five days when QD: The Master Game was shown was for viewers to guess what QD stood for, with the answer being revealed on Friday. To guess this one required knowledge of Latin and/or access to a Latin dictionary, since QD was an abbreviation for the Latin ‘quinque dies’ (or five days) – though if QD had reminded you of the famous abbreviation QED (quod erat demonstratum) you were probably half way there! This illustrates clearly that QD was not going to be just another ordinary quiz show.

So what exactly did QD stand for, apart from yet another quiz game? An ongoing competition that took place during the five days when QD: The Master Game was shown was for viewers to guess what QD stood for, with the answer being revealed on Friday. To guess this one required knowledge of Latin and/or access to a Latin dictionary, since QD was an abbreviation for the Latin ‘quinque dies’ (or five days) – though if QD had reminded you of the famous abbreviation QED (quod erat demonstratum) you were probably half way there! This illustrates clearly that QD was not going to be just another ordinary quiz show.

The presenters were the experienced Tim Brooke-Taylor (who was one of the Goodies – a popular BBC comedy show of the 1970s) and Lisa Aziz, who was the daughter of Khalid Aziz (he was a presenter who had worked for TVS, the ITV company who had also coincidentally produced Ultra Quiz). It seemed obvious that QD: The Master Game‘s format had been influenced by shows like The Krypton Factor along with the aforementioned Ultra Quiz.

The presenters were the experienced Tim Brooke-Taylor (who was one of the Goodies – a popular BBC comedy show of the 1970s) and Lisa Aziz, who was the daughter of Khalid Aziz (he was a presenter who had worked for TVS, the ITV company who had also coincidentally produced Ultra Quiz). It seemed obvious that QD: The Master Game‘s format had been influenced by shows like The Krypton Factor along with the aforementioned Ultra Quiz.

The studio set was fairly elaborate and must have cost quite a lot of time and money to construct (Noel Gay Productions must have been confident of QD being commissioned as a full series). This view of the studio gantry shows the large signs showing the days of the week: the appropriate one being lowered into view. The show also used video effects heavily, with captions spinning into view and an elaborate title sequence (which unfortunately we don’t have in its full form).

The studio set was fairly elaborate and must have cost quite a lot of time and money to construct (Noel Gay Productions must have been confident of QD being commissioned as a full series). This view of the studio gantry shows the large signs showing the days of the week: the appropriate one being lowered into view. The show also used video effects heavily, with captions spinning into view and an elaborate title sequence (which unfortunately we don’t have in its full form).

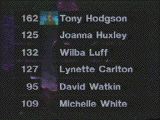

By Friday (the show from which all of these pictures were taken) the number of contestants had been reduced to six, and all of them remained ‘in play’ in order to decide which person was to receive the £5000 prize.

By Friday (the show from which all of these pictures were taken) the number of contestants had been reduced to six, and all of them remained ‘in play’ in order to decide which person was to receive the £5000 prize.

The person with the highest score at the start of Friday’s play (Tony Hodgson) was rarely troubled during the show and went on to win the final prize, though the prize for the contestant who was the most popular with the studio audience had to go to Wilba Luff, who was extrovert yet likeable (Wilba incidentally is a nickname for William). Simply mentioning his name provoked cheers and yelps from the audience; indeed the very concept of “getting to know the contestants” is very much a part of modern ‘reality’ TV formats and QD: The Master Game along with Ultra Quiz employed an “emotional journey” factor as part of their appeal years before programmes like Pop Idol were shown.

The person with the highest score at the start of Friday’s play (Tony Hodgson) was rarely troubled during the show and went on to win the final prize, though the prize for the contestant who was the most popular with the studio audience had to go to Wilba Luff, who was extrovert yet likeable (Wilba incidentally is a nickname for William). Simply mentioning his name provoked cheers and yelps from the audience; indeed the very concept of “getting to know the contestants” is very much a part of modern ‘reality’ TV formats and QD: The Master Game along with Ultra Quiz employed an “emotional journey” factor as part of their appeal years before programmes like Pop Idol were shown.

Fingers on buzzers! The challenges were a mixture of practical tests (see below) and general knowledge/memory tests; one which featured in Friday’s show was that the contestants had to try to memorise the contents of a book full of abbreviations – they were then tested on how much of the book they had actually remembered, though in this case some of the questions could be answered if you had good general knowledge skills. An example question: What does IMF stand for? (Answer: International Monetary Fund.)

Fingers on buzzers! The challenges were a mixture of practical tests (see below) and general knowledge/memory tests; one which featured in Friday’s show was that the contestants had to try to memorise the contents of a book full of abbreviations – they were then tested on how much of the book they had actually remembered, though in this case some of the questions could be answered if you had good general knowledge skills. An example question: What does IMF stand for? (Answer: International Monetary Fund.)

One of the ongoing challenges during the week was for the contestants to design a graphic logo which incorporated QD and the European flag symbol. No prizes for guessing who won this round…the others sadly didn’t stand much of a chance!

One of the ongoing challenges during the week was for the contestants to design a graphic logo which incorporated QD and the European flag symbol. No prizes for guessing who won this round…the others sadly didn’t stand much of a chance!

There must be at least six video copies of QD in existence, since the ‘losers’ (and I’m assuming Tony Hodgson as well) received a video cassette of the entire week’s programmes. The runners-up also each received this neat-looking 10″ television/video combination to play it on. Tony (to win the £5000) then had to answer 30 questions (based on all that he had done during the five days) in three minutes, which he did – but only just.

There must be at least six video copies of QD in existence, since the ‘losers’ (and I’m assuming Tony Hodgson as well) received a video cassette of the entire week’s programmes. The runners-up also each received this neat-looking 10″ television/video combination to play it on. Tony (to win the £5000) then had to answer 30 questions (based on all that he had done during the five days) in three minutes, which he did – but only just.

Tony Hodgson (centre) received his cheque for £5000 at the end – he was asked how he would spend the money. He replied that he would possibly buy a computer for educational purposes for his family (sensible chap that he is). We’ve worked out that at the time his options would have been either a 66 MHz 486 DX/2 PC or Apple Mac Quadra 900 4/160 (the latter leaving no change from £4095, and little change for extras such as a single-speed CD-ROM). Overall the general feeling was that both the contestants, the studio audience, and (hopefully) the viewers had enjoyed these five days in 1991.

Tony Hodgson (centre) received his cheque for £5000 at the end – he was asked how he would spend the money. He replied that he would possibly buy a computer for educational purposes for his family (sensible chap that he is). We’ve worked out that at the time his options would have been either a 66 MHz 486 DX/2 PC or Apple Mac Quadra 900 4/160 (the latter leaving no change from £4095, and little change for extras such as a single-speed CD-ROM). Overall the general feeling was that both the contestants, the studio audience, and (hopefully) the viewers had enjoyed these five days in 1991.

Despite the enthusiasm shown for the pilot, Channel 4 did not commission a full series; the official reason given (according to Tim Brooke-Taylor) was that it would have cost too much. Unofficially its demise may have been down to simply the fact that the relevant commissioning editor wasn’t too keen on the idea in the first place – it was Bill Cotton who came up with the idea, and his friend Michael Grade just happened to be head of Channel 4. QED. Tim also said that “I loved the scary week and cannot speak highly enough of the contestants and the production team. I also have a copy and am proud of the whole thing. But don’t ask me about commissioning editors.”

Despite the enthusiasm shown for the pilot, Channel 4 did not commission a full series; the official reason given (according to Tim Brooke-Taylor) was that it would have cost too much. Unofficially its demise may have been down to simply the fact that the relevant commissioning editor wasn’t too keen on the idea in the first place – it was Bill Cotton who came up with the idea, and his friend Michael Grade just happened to be head of Channel 4. QED. Tim also said that “I loved the scary week and cannot speak highly enough of the contestants and the production team. I also have a copy and am proud of the whole thing. But don’t ask me about commissioning editors.”