In the days before remote controls you had to get out of your seat to make any adjustments to the television set such as adjusting the volume or changing the channel, etc., with the earliest televisions often only being capable of receiving one or two TV channels that were pre-defined for a particular transmitter by the supplying dealer if not done so at the factory.

In the days before remote controls you had to get out of your seat to make any adjustments to the television set such as adjusting the volume or changing the channel, etc., with the earliest televisions often only being capable of receiving one or two TV channels that were pre-defined for a particular transmitter by the supplying dealer if not done so at the factory.

These manual controls often had a great tactile feel to them, especially the VHF channel selector which usually clicked when the knob was turned, and there were numerous other controls for picture adjustment (usually concealed at the sides or rear) which occasionally had to be adjusted due to valve-based circuitry drifting out of alignment, hence the importance of the test card and tuning signal broadcasts prior to the 1980s because they were used to correctly set up a television receiver.

These manual controls often had a great tactile feel to them, especially the VHF channel selector which usually clicked when the knob was turned, and there were numerous other controls for picture adjustment (usually concealed at the sides or rear) which occasionally had to be adjusted due to valve-based circuitry drifting out of alignment, hence the importance of the test card and tuning signal broadcasts prior to the 1980s because they were used to correctly set up a television receiver.

So what were the shops that sold televisions like in the 1950s? The pictures above show a typical example – this was the era before the advent of the big superstore, so lots of receivers were packed into a relatively small shop space (though some department stores also sold televisions, of course). The brand names are mainly unfamiliar, and there’s a complete absence of anything resembling a video recorder. Only one set is showing a picture, and it is Test Card C which was a very common daytime sight in this period.

So what were the shops that sold televisions like in the 1950s? The pictures above show a typical example – this was the era before the advent of the big superstore, so lots of receivers were packed into a relatively small shop space (though some department stores also sold televisions, of course). The brand names are mainly unfamiliar, and there’s a complete absence of anything resembling a video recorder. Only one set is showing a picture, and it is Test Card C which was a very common daytime sight in this period.

The dawn of commercial television (ITV) in 1955 – TV shops in the London and Midlands had signs like this one in the window as retailers promoted the forthcoming ITV service.

The dawn of commercial television (ITV) in 1955 – TV shops in the London and Midlands had signs like this one in the window as retailers promoted the forthcoming ITV service.

If you already had a TV set and wanted ITV as well…prepare to be converted – at a price, of course. In front is a card promoting Ferguson TV’s. “Fine sets those Ferguson’s” was the slogan used at the time.

If you already had a TV set and wanted ITV as well…prepare to be converted – at a price, of course. In front is a card promoting Ferguson TV’s. “Fine sets those Ferguson’s” was the slogan used at the time.

And talking of Ferguson, here’s a selection of Ferguson TV’s and radio’s from the mid 1950s. Ferguson were taken over by the Thorn-EMI empire, which then sold the brand to Thomson (100% owned by the French government), though Thomson has now ceased to exist in the UK. Brands like Alba, Bush and Murphy are now the preserve of retailers and mail order catalogues who basically just use the name for their own-branded products.

And talking of Ferguson, here’s a selection of Ferguson TV’s and radio’s from the mid 1950s. Ferguson were taken over by the Thorn-EMI empire, which then sold the brand to Thomson (100% owned by the French government), though Thomson has now ceased to exist in the UK. Brands like Alba, Bush and Murphy are now the preserve of retailers and mail order catalogues who basically just use the name for their own-branded products.

There were many more brands of television prior to the 1980s, most of which have long since disappeared altogether or absorbed into multinational companies. Here is a picture of the innards of an Ekco television of the mid 1950s.

There were many more brands of television prior to the 1980s, most of which have long since disappeared altogether or absorbed into multinational companies. Here is a picture of the innards of an Ekco television of the mid 1950s.

Moving forward ten years to 1965, and the introduction of one of the first ‘affordable’ video tape recording machines – the Philips EL3400. It was bulky and used an exposed reel of tape, plus it only recorded in black and white despite colour transmissions being available not long afterwards. It also had no tuner or timer facility, so it was only useful with (sometimes) expensive external ancillary equipment such as a separate television tuner or video camera. However, two years before the EL3400 there was a British recorder advertised for sale called the Telcan that was possibly the world’s first domestic video recorder. It could record approximately 20 minutes of 405 line video and audio onto audio tape; a remarkable feat for relatively primitive technology but was a commercial failure presumably due to the short length of its recordings. Only two examples of the Telcan are known to exist nowadays.

Moving forward ten years to 1965, and the introduction of one of the first ‘affordable’ video tape recording machines – the Philips EL3400. It was bulky and used an exposed reel of tape, plus it only recorded in black and white despite colour transmissions being available not long afterwards. It also had no tuner or timer facility, so it was only useful with (sometimes) expensive external ancillary equipment such as a separate television tuner or video camera. However, two years before the EL3400 there was a British recorder advertised for sale called the Telcan that was possibly the world’s first domestic video recorder. It could record approximately 20 minutes of 405 line video and audio onto audio tape; a remarkable feat for relatively primitive technology but was a commercial failure presumably due to the short length of its recordings. Only two examples of the Telcan are known to exist nowadays.

Compared to the Telcan, the EL3400 was a greater success and certainly had its uses, as a group of dancers watch themselves perform on a large video projection screen. The EL3400 did not come cheap because it used a helical scan recording technique also used by professional recorders like the Ampex Quadraplex (the world’s first broadcast quality video recorder), so it was typically found only in large education establishments or used for industrial applications. Also Japanese companies such as Shibaden and Sony were starting to make their presence felt at this time with recorders like the CV-2000 format reel to reel machines which were soon followed by the U-Matic video cassette that proved popular in the industrial and commercial markets.

Compared to the Telcan, the EL3400 was a greater success and certainly had its uses, as a group of dancers watch themselves perform on a large video projection screen. The EL3400 did not come cheap because it used a helical scan recording technique also used by professional recorders like the Ampex Quadraplex (the world’s first broadcast quality video recorder), so it was typically found only in large education establishments or used for industrial applications. Also Japanese companies such as Shibaden and Sony were starting to make their presence felt at this time with recorders like the CV-2000 format reel to reel machines which were soon followed by the U-Matic video cassette that proved popular in the industrial and commercial markets.

The common face of television in the mid to late 1960s – black and white, dual standard (though lots of single-standard 405 line VHF-only televisions remained in use for many years) with separate controls for 405-line VHF and 625-line UHF transmissions. This was required since from 1964 the new BBC2 service was only available on UHF.

The common face of television in the mid to late 1960s – black and white, dual standard (though lots of single-standard 405 line VHF-only televisions remained in use for many years) with separate controls for 405-line VHF and 625-line UHF transmissions. This was required since from 1964 the new BBC2 service was only available on UHF.

1967 saw the arrival of the first mass produced colour TV’s for the UK market, though their high price and initial lack of colour programming (BBC2 only until 1969, few transmitters provided a colour signal and not all programmes were in colour) ensured slow sales to begin with. The picture shows an HMV Colourmaster which was typical of the sets produced in the late 1960s. Find out more about early colour television on the Colour Television page.

1967 saw the arrival of the first mass produced colour TV’s for the UK market, though their high price and initial lack of colour programming (BBC2 only until 1969, few transmitters provided a colour signal and not all programmes were in colour) ensured slow sales to begin with. The picture shows an HMV Colourmaster which was typical of the sets produced in the late 1960s. Find out more about early colour television on the Colour Television page.

Fast forward to 1972 – though a few lucky buyers may have had access to one in 1971 – and the launch of the first ‘proper’ ‘home’ video recorder with an integrated tuner and timer, the Philips N1500. This close-up view (disregard the Sony machine just visible) shows the sloping front panel with (from left to right) a recording level meter, tape transport controls, and the 1 day, 1 event ‘egg timer’ clock. Each large Philips VCR cassette could record up to 30 or 60 (later 80) minutes; the six channel selector buttons are visible above the transport controls. The only thing to put off a potential purchaser – apart from the relatively short running time – was the steep price tag. However the N1500 was not generally available until the end of 1973; earlier it was only sold to schools and corporate customers, and these customers remained the main purchasers of such an expensive device. The less than 90 minutes maximum recording time would have limited its appeal to wealthy people who weren’t interested in recording long movies, therefore it tended to be only specialist shops and upmarket department stores that stocked the recorder.

Fast forward to 1972 – though a few lucky buyers may have had access to one in 1971 – and the launch of the first ‘proper’ ‘home’ video recorder with an integrated tuner and timer, the Philips N1500. This close-up view (disregard the Sony machine just visible) shows the sloping front panel with (from left to right) a recording level meter, tape transport controls, and the 1 day, 1 event ‘egg timer’ clock. Each large Philips VCR cassette could record up to 30 or 60 (later 80) minutes; the six channel selector buttons are visible above the transport controls. The only thing to put off a potential purchaser – apart from the relatively short running time – was the steep price tag. However the N1500 was not generally available until the end of 1973; earlier it was only sold to schools and corporate customers, and these customers remained the main purchasers of such an expensive device. The less than 90 minutes maximum recording time would have limited its appeal to wealthy people who weren’t interested in recording long movies, therefore it tended to be only specialist shops and upmarket department stores that stocked the recorder.

The N1500 was replaced by the N1502 in 1976, which was basically an updated N1500 with a more modern case, a digital timer and a few extra features like a ‘Stop motion’ button which froze the picture on-screen. Indeed the N1502 looked almost identical to the forthcoming N1700 which was known to be in development at the time, so the N1502 was probably produced as a stop-gap.

Space oddity…Anyone who walked into the television department of a large upmarket department store (such as Harrods in London) in the 1970s may have been confronted with this space helmet-shaped television known as the Keracolor. This rare model is a design classic, and with 1970s style back in fashion a reconditioned Keracolor retailed in 1998 for as much as £800. Produced in Northwich, Cheshire, there were colour and monochrome versions as well as a smaller portable version, and at least the colour sets used a Decca chassis supported by stickle bricks. (Yes, stickle bricks!) The Keracolor brand was revived much more recently but sadly failed to make a discernible impact on the television world, even minus the stickle bricks.

Send in the clones…the 1970s saw the rise of Japanese manufacturers in Europe and elsewhere, displacing many established companies both in the UK and abroad. Many of the Japanese products from this period were heavily influenced by European models; the JVC Videosphere pictured here being another helmet-based design. The right-hand picture shows the set’s controls – the thumbwheel controls (from left to right) are for brightness, contrast, and off-on/volume, plus rotary VHF and UHF tuning controls. The example shown here is rare since this monochrome TV usually had an orange casing; even so, compared to the Keracolor it is relatively affordable with a 1998 price of £330. Incidentally, the pictures of both this and the Keracolor were taken from BBC Two’s The Antiques Show.

1976 was the year that teletext receivers were sold in UK shops for the very first time, enabling news and information to be displayed on a television screen at a push of a button, but they still weren’t widely available for at least another year. There had been a public teletext service operational since September 1974, but at the start there were only three teletext receivers in existence and they couldn’t be bought in shops, though an electronics magazine published a guide to building your own teletext decoder in 1975 for those who were technically proficient enough to build one from scratch. The Labgear external decoder was the first to be manufactured and sold to the public, with four channels selectable using push buttons on the front panel and a wired remote control used to select pages and other teletext features such as hold and reveal.

CEEFAX had been demonstrated by the BBC to the public as early as a news report on 23 October 1972, but IBA engineers had been independently working on their own ORACLE system therefore it took two years for the two incompatible systems to be reworked into a single standard known as teletext and for broadcasts to commence, with the acronyms CEEFAX and ORACLE being used as the two brand names for the BBC and IBA (ITV) services using the same teletext standard. The falling price of digital electronics made teletext much more affordable during the 1980s and proved to be popular in the UK, remaining in use until it was made obsolete by the analogue TV transmission switch off.

CEEFAX had been demonstrated by the BBC to the public as early as a news report on 23 October 1972, but IBA engineers had been independently working on their own ORACLE system therefore it took two years for the two incompatible systems to be reworked into a single standard known as teletext and for broadcasts to commence, with the acronyms CEEFAX and ORACLE being used as the two brand names for the BBC and IBA (ITV) services using the same teletext standard. The falling price of digital electronics made teletext much more affordable during the 1980s and proved to be popular in the UK, remaining in use until it was made obsolete by the analogue TV transmission switch off.

1977 saw the mass market arrival of a piece of technology that would prove to be very popular for more than 20 years and is still used by many people today, the VCR… (Pictures copyright: Philips Electronics.)

Before the video cassette recorder (VCR) became popular during the 1980s, it was necessary to explain to potential customers exactly what a VCR was and what it could actually do, and those potential customers may not be mechanically-minded either, so the best person to explain what a VCR did in layman’s terms is someone who is recognisably an expert in television but who isn’t necessarily an expert in things mechanical, namely someone like the writer and presenter Denis Norden, therefore Philips were extremely lucky to be able to have Norden present their promotional video demonstrating the benefits of their brand new N1700 VCR. It’s interesting that Philips chose to describe their VCR as simply a “Time Machine” as opposed to a “Television Time Machine” which would have been a much more precise description of what it could do if perhaps a less eye-catching expression.

Before the video cassette recorder (VCR) became popular during the 1980s, it was necessary to explain to potential customers exactly what a VCR was and what it could actually do, and those potential customers may not be mechanically-minded either, so the best person to explain what a VCR did in layman’s terms is someone who is recognisably an expert in television but who isn’t necessarily an expert in things mechanical, namely someone like the writer and presenter Denis Norden, therefore Philips were extremely lucky to be able to have Norden present their promotional video demonstrating the benefits of their brand new N1700 VCR. It’s interesting that Philips chose to describe their VCR as simply a “Time Machine” as opposed to a “Television Time Machine” which would have been a much more precise description of what it could do if perhaps a less eye-catching expression.

The N1700 recorded television broadcasts onto the same size cassette tapes as the N1500, with up to 2 hours of record and play time initially available (Long Play = LP) compared to the 1 hour duration offered by the earlier N1500 series machines (including the N1502 which looked very similar to the N1700); this was achieved by slowing the tape speed down and using improved electronics, therefore recordings were incompatible between VCR-LP and the earlier VCR machines. Even longer tapes were later introduced, enabling 3 hours of recording time on VCR-LP recorders in order to compete with the new VHS and Betamax recorders offered by Japanese manufacturers that were launched in the UK during 1978. (Betamax and VHS had already launched in Japanese/US NTSC markets; 1975 for Betamax and 1976 for VHS respectively, so Philips knew that competition for their product was soon to appear in Europe.)

The N1700 recorded television broadcasts onto the same size cassette tapes as the N1500, with up to 2 hours of record and play time initially available (Long Play = LP) compared to the 1 hour duration offered by the earlier N1500 series machines (including the N1502 which looked very similar to the N1700); this was achieved by slowing the tape speed down and using improved electronics, therefore recordings were incompatible between VCR-LP and the earlier VCR machines. Even longer tapes were later introduced, enabling 3 hours of recording time on VCR-LP recorders in order to compete with the new VHS and Betamax recorders offered by Japanese manufacturers that were launched in the UK during 1978. (Betamax and VHS had already launched in Japanese/US NTSC markets; 1975 for Betamax and 1976 for VHS respectively, so Philips knew that competition for their product was soon to appear in Europe.)

So using the N1700 is as straightforward as: (a) Switching it on; (b) Selecting a TV channel to record from, using the buttons marked 1 to 8; (c) Press the Record and Play buttons down together to start the recording; (d) Press the Stop button to stop the recording. Simple! (The N1500 was nearly as easy to use with perhaps the added complication of setting an audio record level control.)

Just like the earlier N1500/N1502 models, the N1700 VCR recorded television broadcasts onto removable cassette tapes, therefore you had to have inserted a tape into the machine in the first place and ensured that there was enough free space on the tape for a new recording, if necessary rewinding the tape to a suitable point (or the beginning) as shown here, but anyone already familiar with audio cassette recording as most people were at that point during the 1970s would instinctively understand such concepts even if people under the age of 25 nowadays would be even more clueless about VCR’s as the average person would have been in the 1970s. The N1700 did the job it was designed to do on a basic level, but it had no remote control and no picture search facility so you had to make use of a mechanical tape counter and/or the tape compartment window to work out exactly how much tape was left for recording/playback.

Just like the earlier N1500/N1502 models, the N1700 VCR recorded television broadcasts onto removable cassette tapes, therefore you had to have inserted a tape into the machine in the first place and ensured that there was enough free space on the tape for a new recording, if necessary rewinding the tape to a suitable point (or the beginning) as shown here, but anyone already familiar with audio cassette recording as most people were at that point during the 1970s would instinctively understand such concepts even if people under the age of 25 nowadays would be even more clueless about VCR’s as the average person would have been in the 1970s. The N1700 did the job it was designed to do on a basic level, but it had no remote control and no picture search facility so you had to make use of a mechanical tape counter and/or the tape compartment window to work out exactly how much tape was left for recording/playback.

The N1700 did have a basic digital timer capable of recording one programme that had a start time at some point during the next three days, which at least was an improvement over the first Philips VCR N1500 that could only manage a recording start time during the next 24 hours (and was a mechanical timer similar to that used on an old cooker); the N1700 timer was set using a sliding control which was moved one step at a time from left to right, setting the day, start time, and programme duration in that order. Simple and relatively foolproof if not the last word in sophistication, but anything more complex would have made the N1700 too expensive when Philips was trying to keep the overall product cost down.

The N1700 did have a basic digital timer capable of recording one programme that had a start time at some point during the next three days, which at least was an improvement over the first Philips VCR N1500 that could only manage a recording start time during the next 24 hours (and was a mechanical timer similar to that used on an old cooker); the N1700 timer was set using a sliding control which was moved one step at a time from left to right, setting the day, start time, and programme duration in that order. Simple and relatively foolproof if not the last word in sophistication, but anything more complex would have made the N1700 too expensive when Philips was trying to keep the overall product cost down.

If you were really wealthy in the 1970s, you could not only afford a VCR but also have the disposable income to buy an optional camera to plug in the back of it, meaning that you could record home movies on your VCR as long as the lead between camera and VCR was long enough to reach where you wanted to record; fine for recording children playing in the living room or perhaps in the garden from the patio but useless for many other parts of the house or outside. Also the cheap cameras only recorded in black and white, therefore colour recording required additional expense as well as good lighting because the camera tubes weren’t very sensitive to light, so that candlelit dinner party recording may turn out to be a complete washout unless very bright lights were used.

If you were really wealthy in the 1970s, you could not only afford a VCR but also have the disposable income to buy an optional camera to plug in the back of it, meaning that you could record home movies on your VCR as long as the lead between camera and VCR was long enough to reach where you wanted to record; fine for recording children playing in the living room or perhaps in the garden from the patio but useless for many other parts of the house or outside. Also the cheap cameras only recorded in black and white, therefore colour recording required additional expense as well as good lighting because the camera tubes weren’t very sensitive to light, so that candlelit dinner party recording may turn out to be a complete washout unless very bright lights were used.

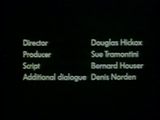

Denis Norden not only presented the promotion but contributed to its script, being a famous scriptwriter himself having worked alongside Frank Muir amongst others in the past, and this showed in the humourous touches employed including various interactions with his wife (whom you don’t actually see), such as getting ready to go out therefore being able to set the VCR to record something whilst away, etc.; this promotion wasn’t just a factual explanation of how to use a video cassette recorder.

After the practical lesson there were three films intended to be shown in shops for demonstration purposes; skiing, canoeing and land yachting. The skiing film had an accompanying musical soundtrack (Psyche Rock by Pierre Henry) whilst the others featured a natural soundtrack, though there’s another version of the canoeing film with Psyche Rock music also used as a shop demonstration for the N1700.

Grundig produced its own SVR format based on Philips VCR-LP tapes but offering even longer recording times, though it wasn’t popular due to poor availability combined with a near absence of pre-recorded tapes. By 1978 the Japanese-developed Betamax (Sony) and VHS (JVC) videotape formats reached the UK, both offering longer recording times and a wider choice of recorders from different manufacturers compared to Philips’s VCR-LP format. Philips countered by offering a 3 hour tape for the N1700 and the Philips recorder was still the best-selling VCR in 1979 despite the new competition. Philips was also developing a new Video 2000 tape format which unfortunately didn’t reach the market until 1980 when VHS in particular was rapidly becoming established due to greater support from dealers and popularity with schools.

There had been occasional attempts at breakfast television in the UK previously (Yorkshire Television’s Good Morning Calendar for ITV (Yorkshire region only) in 1977 and later on BBC1’s Swap Shop tried an earlier start with AM-UK), but the market for breakfast television was still considered to be limited in the UK because it was thought that most people might be too busy to watch television at that time of the day. Once a commercial breakfast television franchise had been created and awarded to TV-am in 1980 alongside other ITV franchise changes, TV-am’s launch was scheduled for 1 February 1983 in order to avoid the other ITV franchise changes at the start of 1982 as well as the launch of Channel 4 the following November. However the BBC decided to get in first with a ‘spoiler’ programme, namely Breakfast Time on BBC1 which launched a month earlier, and much to TV-am’s dismay (they were due on air shortly) it was not the serious news programme some thought it might have been, but was a direct competitor which helped to hit TV-am’s initial viewing figures badly. Later on, Breakfast Time was scrapped and replaced with a more serious BBC Breakfast News format.

There had been occasional attempts at breakfast television in the UK previously (Yorkshire Television’s Good Morning Calendar for ITV (Yorkshire region only) in 1977 and later on BBC1’s Swap Shop tried an earlier start with AM-UK), but the market for breakfast television was still considered to be limited in the UK because it was thought that most people might be too busy to watch television at that time of the day. Once a commercial breakfast television franchise had been created and awarded to TV-am in 1980 alongside other ITV franchise changes, TV-am’s launch was scheduled for 1 February 1983 in order to avoid the other ITV franchise changes at the start of 1982 as well as the launch of Channel 4 the following November. However the BBC decided to get in first with a ‘spoiler’ programme, namely Breakfast Time on BBC1 which launched a month earlier, and much to TV-am’s dismay (they were due on air shortly) it was not the serious news programme some thought it might have been, but was a direct competitor which helped to hit TV-am’s initial viewing figures badly. Later on, Breakfast Time was scrapped and replaced with a more serious BBC Breakfast News format. TV-am followed swiftly afterwards, launched with a barrage of publicity on 1st February 1983. It featured a mixture of familiar and unfamiliar presenters (David Frost being the key figure) and had a ‘bright and breezy’ approach to waking the nation up in the morning. Expectations were set high for the new service, but in reality there were several unanswered questions; most notably just how many people in the UK were prepared to watch television instead of listening to the radio at that time of day especially given the BBC1 competition.

TV-am followed swiftly afterwards, launched with a barrage of publicity on 1st February 1983. It featured a mixture of familiar and unfamiliar presenters (David Frost being the key figure) and had a ‘bright and breezy’ approach to waking the nation up in the morning. Expectations were set high for the new service, but in reality there were several unanswered questions; most notably just how many people in the UK were prepared to watch television instead of listening to the radio at that time of day especially given the BBC1 competition. The main breakfast show’s title Good Morning Britain – a title since revived by ITV but with no connection to the TV-am original – deliberately echoed the similar US programme Good Morning America, and the British show had much in common with its American counterpart, such as the use of an on-screen clock, and the use of a caption to tell viewers what was to follow the commercial break. TV-am also made other programmes to show during its allocated time slot, such as Daybreak (the same title also used much later by ITV for its unconnected breakfast show), Data Run, and Wacaday presented by Timmy Mallet.

The main breakfast show’s title Good Morning Britain – a title since revived by ITV but with no connection to the TV-am original – deliberately echoed the similar US programme Good Morning America, and the British show had much in common with its American counterpart, such as the use of an on-screen clock, and the use of a caption to tell viewers what was to follow the commercial break. TV-am also made other programmes to show during its allocated time slot, such as Daybreak (the same title also used much later by ITV for its unconnected breakfast show), Data Run, and Wacaday presented by Timmy Mallet. After the commercial break had finished, this caption was shown, which also features the on-screen clock (showing ten past nine, in the bottom-right hand corner). By April TV-am’s future looked bleak – viewing figures had plummeted to about 100,000, partly courtesy of what was considered to be surprisingly strong competition from Breakfast Time. (Anyone remember Russell Grant’s horoscopes?) So Greg Dyke was brought in from London Weekend Television to try and improve things – David Frost was replaced by Nick Owen and TV-am went downmarket, successfully reversing the drop.

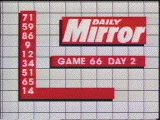

After the commercial break had finished, this caption was shown, which also features the on-screen clock (showing ten past nine, in the bottom-right hand corner). By April TV-am’s future looked bleak – viewing figures had plummeted to about 100,000, partly courtesy of what was considered to be surprisingly strong competition from Breakfast Time. (Anyone remember Russell Grant’s horoscopes?) So Greg Dyke was brought in from London Weekend Television to try and improve things – David Frost was replaced by Nick Owen and TV-am went downmarket, successfully reversing the drop. At the time there was a craze among tabloid newspapers for running bingo competitions, so a bright idea was to tell the viewers what the day’s numbers were so they didn’t have to buy the newspaper. Occasionally the numbers were misread, though any mistakes were inevitably corrected. Nick Owen bizarrely had to dress up in a beefeater’s outfit and blow a trumpet to introduce this part of the programme!

At the time there was a craze among tabloid newspapers for running bingo competitions, so a bright idea was to tell the viewers what the day’s numbers were so they didn’t have to buy the newspaper. Occasionally the numbers were misread, though any mistakes were inevitably corrected. Nick Owen bizarrely had to dress up in a beefeater’s outfit and blow a trumpet to introduce this part of the programme! Roland Rat was also introduced as part of the April shake-up. Created by David Claridge and introduced to TV-am by Anne ‘Teletubbies’ Wood, Roland Rat proved to be very popular with the viewers and gave the breakfast start-up a much needed shot in the arm. Rat mania even spawned two UK Top 40 records in 1983/4 – Rat Rapping and Love Me Tender. Anne Diamond also had to work alongside ‘Roland Rat Superstar’ which must have been a tough act to keep up with! Thankfully Roland Rat is still very much alive today…

Roland Rat was also introduced as part of the April shake-up. Created by David Claridge and introduced to TV-am by Anne ‘Teletubbies’ Wood, Roland Rat proved to be very popular with the viewers and gave the breakfast start-up a much needed shot in the arm. Rat mania even spawned two UK Top 40 records in 1983/4 – Rat Rapping and Love Me Tender. Anne Diamond also had to work alongside ‘Roland Rat Superstar’ which must have been a tough act to keep up with! Thankfully Roland Rat is still very much alive today… The weather forecast was presented by Commander Philpott, whose style was certainly different from the competition – come to think of it anything else past or present. ‘Stiff upper lip British’ was perhaps the best way to describe the Commander’s technique.

The weather forecast was presented by Commander Philpott, whose style was certainly different from the competition – come to think of it anything else past or present. ‘Stiff upper lip British’ was perhaps the best way to describe the Commander’s technique. This caption was shown at the end of the programme, with one egg cup added to the picture for each year since 1983 (1984 = two egg cups displayed, etc.), though in later years only a few of the cups actually appeared in the caption. TV-am was a programme contractor in its own right, and was independent of the other companies that formed the ITV network.

This caption was shown at the end of the programme, with one egg cup added to the picture for each year since 1983 (1984 = two egg cups displayed, etc.), though in later years only a few of the cups actually appeared in the caption. TV-am was a programme contractor in its own right, and was independent of the other companies that formed the ITV network. TV-am also promoted its shows at other times on the ITV network, with this example promoting Chris Tarrant and Roland Rat appearing on Christmas Day 1984 and a Princess Anne interview shown on Boxing Day.

TV-am also promoted its shows at other times on the ITV network, with this example promoting Chris Tarrant and Roland Rat appearing on Christmas Day 1984 and a Princess Anne interview shown on Boxing Day. TV-am did its own news gathering in early years, but later on the news was provided by Rupert Murdoch’s Sky News until TV-am’s demise at the end of 1992.

TV-am did its own news gathering in early years, but later on the news was provided by Rupert Murdoch’s Sky News until TV-am’s demise at the end of 1992. TV-am were among the losers when the ITV broadcasting franchises were reviewed in 1991, so from the 1st January 1993 TV-am was replaced by GMTV. This picture was the very last to be transmitted by TV-am; the colour of the main scene was faded moments before the picture faded abruptly. An era had come to an end.

TV-am were among the losers when the ITV broadcasting franchises were reviewed in 1991, so from the 1st January 1993 TV-am was replaced by GMTV. This picture was the very last to be transmitted by TV-am; the colour of the main scene was faded moments before the picture faded abruptly. An era had come to an end. TV-am’s replacement, GMTV (which prior to 2004 was part-owned by Carlton, Granada and Disney) to begin with tried to establish its own identity but slowly evolved over the years into something that looks very similar to TV-am, and also provided signed news and additional cartoons on ITV2 during the same timeslot for a while under the GMTV2 banner, though (like TV-am) GMTV and ITV are technically two separate entities that just happen to use the same channel. Whilst GMTV was a separate entity from ITV, if ITV wanted to ‘borrow’ time from GMTV in order (for example) to show a sporting event, it had to compensate GMTV somehow (either financially or by giving GMTV additional air time) as a result. GMTV ceased to exist after ITV plc bought out Disney’s share of the broadcaster and what was still a physically separate commercial television franchise became fully integrated into the ITV channel as Daybreak. Later on the separate breakfast franchise was abolished by the Digital Economy Act and Daybreak has since been replaced by Good Morning Britain; nothing to do with TV-am but using the same name as TV-am’s original breakfast show.

TV-am’s replacement, GMTV (which prior to 2004 was part-owned by Carlton, Granada and Disney) to begin with tried to establish its own identity but slowly evolved over the years into something that looks very similar to TV-am, and also provided signed news and additional cartoons on ITV2 during the same timeslot for a while under the GMTV2 banner, though (like TV-am) GMTV and ITV are technically two separate entities that just happen to use the same channel. Whilst GMTV was a separate entity from ITV, if ITV wanted to ‘borrow’ time from GMTV in order (for example) to show a sporting event, it had to compensate GMTV somehow (either financially or by giving GMTV additional air time) as a result. GMTV ceased to exist after ITV plc bought out Disney’s share of the broadcaster and what was still a physically separate commercial television franchise became fully integrated into the ITV channel as Daybreak. Later on the separate breakfast franchise was abolished by the Digital Economy Act and Daybreak has since been replaced by Good Morning Britain; nothing to do with TV-am but using the same name as TV-am’s original breakfast show. They say that restaurant critics make lousy chefs…but do television critics make lousy television? Victor Lewis-Smith is an established television critic (for the London Evening Standard) as well as writing for several other publications, and in the past Lewis-Smith had presented TV programmes such Inside Victor Lewis-Smith plus features within other shows such as BBC2’s TV Hell. His newspaper columns don’t just cover television but also nostalgia, so it’s only logical that he should also have a strong interest in television nostalgia.

They say that restaurant critics make lousy chefs…but do television critics make lousy television? Victor Lewis-Smith is an established television critic (for the London Evening Standard) as well as writing for several other publications, and in the past Lewis-Smith had presented TV programmes such Inside Victor Lewis-Smith plus features within other shows such as BBC2’s TV Hell. His newspaper columns don’t just cover television but also nostalgia, so it’s only logical that he should also have a strong interest in television nostalgia.

From this you might have deduced that TV Offal pokes fun not only at programmes but also at programming formats and ‘celebrities’, as well as anything else that could related to television and broadcasting culture such as test cards and ident (station identification) sequences. Despite the parodying tone, it becomes rapidly self-evident that Victor himself actually revels in these ephemera of TV culture, though it’s equally obvious that he really means it when he mocks celebrities such as Noel Edmonds or Vanessa Feltz. The audio used in the link sequences is almost uniquely (for television) styled in the form of radio jingles, notably jingles specially commissioned from the world-famous American jingle producers JAM.

From this you might have deduced that TV Offal pokes fun not only at programmes but also at programming formats and ‘celebrities’, as well as anything else that could related to television and broadcasting culture such as test cards and ident (station identification) sequences. Despite the parodying tone, it becomes rapidly self-evident that Victor himself actually revels in these ephemera of TV culture, though it’s equally obvious that he really means it when he mocks celebrities such as Noel Edmonds or Vanessa Feltz. The audio used in the link sequences is almost uniquely (for television) styled in the form of radio jingles, notably jingles specially commissioned from the world-famous American jingle producers JAM. It seemed that viewers and critics other than Victor himself liked the pilot show, so Channel 4 went ahead with commissioning a series of six half-hour programmes which ran from May 22nd 1998, shown on Friday evenings at 11 pm. Late night Channel 4 is not exactly viewing suitable for children (as programmes such as Eurotrash or The Word have graphically illustrated), so TV Offal was able to use this scheduling to its advantage in order to show the sort of things that would have made ‘clean-up tv’ campaigner Mary Whitehouse reach for the typewriter…

It seemed that viewers and critics other than Victor himself liked the pilot show, so Channel 4 went ahead with commissioning a series of six half-hour programmes which ran from May 22nd 1998, shown on Friday evenings at 11 pm. Late night Channel 4 is not exactly viewing suitable for children (as programmes such as Eurotrash or The Word have graphically illustrated), so TV Offal was able to use this scheduling to its advantage in order to show the sort of things that would have made ‘clean-up tv’ campaigner Mary Whitehouse reach for the typewriter… Much of the source material used by TV Offal comes from a little-known (outside of the TV industry) phenomenon known as ‘Christmas tapes’. These are unofficial compilations of programme and continuity-related material made by TV station staff in their spare time which often comprised of a collection of ‘outtakes’ (presenters fluffing their lines, etc.) compiled from such incidents recorded during the previous year but also may include clips specially recorded for the tape, originally intended for the staff’s own amusement only and not for transmission; the clip showing the Rainbow (kids’ TV show) team letting off steam with ‘the bad language’ being a prime example. The excerpt used in the pilot episode came from a Christmas 1978 tape produced by Thames Television staff.

Much of the source material used by TV Offal comes from a little-known (outside of the TV industry) phenomenon known as ‘Christmas tapes’. These are unofficial compilations of programme and continuity-related material made by TV station staff in their spare time which often comprised of a collection of ‘outtakes’ (presenters fluffing their lines, etc.) compiled from such incidents recorded during the previous year but also may include clips specially recorded for the tape, originally intended for the staff’s own amusement only and not for transmission; the clip showing the Rainbow (kids’ TV show) team letting off steam with ‘the bad language’ being a prime example. The excerpt used in the pilot episode came from a Christmas 1978 tape produced by Thames Television staff. Every TV Offal featured one or two “Kamikaze Karaoke” sketches, whereby some of the most famous popular/classical music acts are seen performing, but their voices substituted with singing that is off-key/has different lyrics/etc., superimposed upon the same or similar musical backing. Guaranteed to bring the most egoistical superstar crashing down to earth, singers and acts which had been given the “This is what he sounds like to me” treatment included Pavarotti, Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley, Elton John, Bob Marley, Nigel Kennedy, Vanessa-Mae and that Manchester foursome Oasis.

Every TV Offal featured one or two “Kamikaze Karaoke” sketches, whereby some of the most famous popular/classical music acts are seen performing, but their voices substituted with singing that is off-key/has different lyrics/etc., superimposed upon the same or similar musical backing. Guaranteed to bring the most egoistical superstar crashing down to earth, singers and acts which had been given the “This is what he sounds like to me” treatment included Pavarotti, Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley, Elton John, Bob Marley, Nigel Kennedy, Vanessa-Mae and that Manchester foursome Oasis. Probably the most controversial of TV Offal‘s regular features is the Gay Daleks: “They’re camp! They exterminate! Better watch your backs! It’s the Gay Daleks!” You either feel that the sketches are crude, tasteless and offensive, or they’re a splendid parody of both the Daleks and of gay cultural stereotypes; late night Channel 4 viewers (on the whole) would interpret them as the latter which is probably just as well given the content. Apparently they were popular with the gay community, though later attempts to produce a cartoon series based on the Gay Daleks did not materialise due to rights issues involving the Terry Nation estate.

Probably the most controversial of TV Offal‘s regular features is the Gay Daleks: “They’re camp! They exterminate! Better watch your backs! It’s the Gay Daleks!” You either feel that the sketches are crude, tasteless and offensive, or they’re a splendid parody of both the Daleks and of gay cultural stereotypes; late night Channel 4 viewers (on the whole) would interpret them as the latter which is probably just as well given the content. Apparently they were popular with the gay community, though later attempts to produce a cartoon series based on the Gay Daleks did not materialise due to rights issues involving the Terry Nation estate. Another semi-regular feature that straddles the commercial break is “Assassination of the Week”. This sketch parodies the voyeurism that certain programmes seem to exhibit, namely, before the commercial break an assassination attempt is shown, and viewers are invited to guess “did they live or are they worm-food?”. After the break the rest of the film is shown and the answer is given, though there was a twist when the assassination of JFK was covered. Other politicians featured included Imelda Marcos, the woman which had a very large shoe collection.

Another semi-regular feature that straddles the commercial break is “Assassination of the Week”. This sketch parodies the voyeurism that certain programmes seem to exhibit, namely, before the commercial break an assassination attempt is shown, and viewers are invited to guess “did they live or are they worm-food?”. After the break the rest of the film is shown and the answer is given, though there was a twist when the assassination of JFK was covered. Other politicians featured included Imelda Marcos, the woman which had a very large shoe collection. TV Offal often featured “The Pilots that Crashed”; one-off programmes that never got any further than the pilot episode or shows that had a very limited run. Perhaps controversially, the show featured “The Development of the Television Test Card” in show 2 which wasn’t a failed pilot programme; indeed it was a one-off show (made in 1985) aimed at a specialist audience as reference material therefore it was never intended to be commissioned as a broadcast series. But it featured one of Victor’s favourite subjects (as anyone seeing any earlier material of his would testify) so he couldn’t possibly ignore it!

TV Offal often featured “The Pilots that Crashed”; one-off programmes that never got any further than the pilot episode or shows that had a very limited run. Perhaps controversially, the show featured “The Development of the Television Test Card” in show 2 which wasn’t a failed pilot programme; indeed it was a one-off show (made in 1985) aimed at a specialist audience as reference material therefore it was never intended to be commissioned as a broadcast series. But it featured one of Victor’s favourite subjects (as anyone seeing any earlier material of his would testify) so he couldn’t possibly ignore it! TV Offal regularly featured clips from the archives of student or hospital television stations, often featuring celebrities either before they became famous or making a guest appearence. Famous people featured included Michaela Strachan, Phillippa Forrester, and Christopher Biggins. The picture is taken from the ident used in 1969 of STOIC – Student Television of Imperial College (London).

TV Offal regularly featured clips from the archives of student or hospital television stations, often featuring celebrities either before they became famous or making a guest appearence. Famous people featured included Michaela Strachan, Phillippa Forrester, and Christopher Biggins. The picture is taken from the ident used in 1969 of STOIC – Student Television of Imperial College (London). A TV Offal show wouldn’t be complete without one of Victor Lewis-Smith’s “specialities”, the wind-up phone call. He calls a famous person or organisation pretending to be someone else, with either hilarious or deeply embarrassing results. “Victims” included Carlton Television in the first show, the late Hughie Green and Mary Whitehouse. However the alleged ‘call’ to Mary Whitehouse landed Victor in a spot of bother, and it’s also interesting to note that phone calls of this nature are no longer permitted to be broadcast on UK television under Ofcom regulations.

A TV Offal show wouldn’t be complete without one of Victor Lewis-Smith’s “specialities”, the wind-up phone call. He calls a famous person or organisation pretending to be someone else, with either hilarious or deeply embarrassing results. “Victims” included Carlton Television in the first show, the late Hughie Green and Mary Whitehouse. However the alleged ‘call’ to Mary Whitehouse landed Victor in a spot of bother, and it’s also interesting to note that phone calls of this nature are no longer permitted to be broadcast on UK television under Ofcom regulations. The show is produced by Victor’s own production company, Associated-Rediffusion Television Ltd., which happens also to be the name of the ITV contractor that served London weekdays from 1955-1968. Victor bought the rights many years ago when it was simply ‘gathering dust’, and he even featured the voice of Redvers Kyle who was a regular continuity announcer for A-R in the 1950s (amongst others), in show 4. There will never be a commercial release (DVD/video download, etc.) of the TV Offal series because producer John Warburton found it difficult enough gaining copyright clearance for many of the clips used simply for television transmission.

The show is produced by Victor’s own production company, Associated-Rediffusion Television Ltd., which happens also to be the name of the ITV contractor that served London weekdays from 1955-1968. Victor bought the rights many years ago when it was simply ‘gathering dust’, and he even featured the voice of Redvers Kyle who was a regular continuity announcer for A-R in the 1950s (amongst others), in show 4. There will never be a commercial release (DVD/video download, etc.) of the TV Offal series because producer John Warburton found it difficult enough gaining copyright clearance for many of the clips used simply for television transmission. So, to paraphrase the “Assassination of the Week” feature, what happened next? The answer is the cleverly-titled Ads Infinitum – two series of ten-minute programmes shown on BBC2 (the first series in 1998), which (as the title suggests) are all about television or cinema adverts. And as for TV Offal itself, the only repeat showings were some compilation programmes (‘the best of’ or ‘the worst of’, depending on your point of view.) subsequently shown on Channel 4. These days Victor Lewis-Smith is occasionally still involved with television production and continues to be a newspaper TV critic and columnist for publications such as Private Eye; recent productions include Alchemists of Sound for BBC Four, You’re Fayed! for Channel 4 and a documentary The Undiscovered Peter Cook for BBC Four featuring some of the satirist’s personal diaries, letters, photographs and recordings.

So, to paraphrase the “Assassination of the Week” feature, what happened next? The answer is the cleverly-titled Ads Infinitum – two series of ten-minute programmes shown on BBC2 (the first series in 1998), which (as the title suggests) are all about television or cinema adverts. And as for TV Offal itself, the only repeat showings were some compilation programmes (‘the best of’ or ‘the worst of’, depending on your point of view.) subsequently shown on Channel 4. These days Victor Lewis-Smith is occasionally still involved with television production and continues to be a newspaper TV critic and columnist for publications such as Private Eye; recent productions include Alchemists of Sound for BBC Four, You’re Fayed! for Channel 4 and a documentary The Undiscovered Peter Cook for BBC Four featuring some of the satirist’s personal diaries, letters, photographs and recordings.

In the days before remote controls you had to get out of your seat to make any adjustments to the television set such as adjusting the volume or changing the channel, etc., with the earliest televisions often only being capable of receiving one or two TV channels that were pre-defined for a particular transmitter by the supplying dealer if not done so at the factory.

In the days before remote controls you had to get out of your seat to make any adjustments to the television set such as adjusting the volume or changing the channel, etc., with the earliest televisions often only being capable of receiving one or two TV channels that were pre-defined for a particular transmitter by the supplying dealer if not done so at the factory. These manual controls often had a great tactile feel to them, especially the VHF channel selector which usually clicked when the knob was turned, and there were numerous other controls for picture adjustment (usually concealed at the sides or rear) which occasionally had to be adjusted due to valve-based circuitry drifting out of alignment, hence the importance of the test card and tuning signal broadcasts prior to the 1980s because they were used to correctly set up a television receiver.

These manual controls often had a great tactile feel to them, especially the VHF channel selector which usually clicked when the knob was turned, and there were numerous other controls for picture adjustment (usually concealed at the sides or rear) which occasionally had to be adjusted due to valve-based circuitry drifting out of alignment, hence the importance of the test card and tuning signal broadcasts prior to the 1980s because they were used to correctly set up a television receiver.

So what were the shops that sold televisions like in the 1950s? The pictures above show a typical example – this was the era before the advent of the big superstore, so lots of receivers were packed into a relatively small shop space (though some department stores also sold televisions, of course). The brand names are mainly unfamiliar, and there’s a complete absence of anything resembling a video recorder. Only one set is showing a picture, and it is Test Card C which was a very common daytime sight in this period.

So what were the shops that sold televisions like in the 1950s? The pictures above show a typical example – this was the era before the advent of the big superstore, so lots of receivers were packed into a relatively small shop space (though some department stores also sold televisions, of course). The brand names are mainly unfamiliar, and there’s a complete absence of anything resembling a video recorder. Only one set is showing a picture, and it is Test Card C which was a very common daytime sight in this period. The dawn of commercial television (ITV) in 1955 – TV shops in the London and Midlands had signs like this one in the window as retailers promoted the forthcoming ITV service.

The dawn of commercial television (ITV) in 1955 – TV shops in the London and Midlands had signs like this one in the window as retailers promoted the forthcoming ITV service. If you already had a TV set and wanted ITV as well…prepare to be converted – at a price, of course. In front is a card promoting Ferguson TV’s. “Fine sets those Ferguson’s” was the slogan used at the time.

If you already had a TV set and wanted ITV as well…prepare to be converted – at a price, of course. In front is a card promoting Ferguson TV’s. “Fine sets those Ferguson’s” was the slogan used at the time. And talking of Ferguson, here’s a selection of Ferguson TV’s and radio’s from the mid 1950s. Ferguson were taken over by the Thorn-EMI empire, which then sold the brand to Thomson (100% owned by the French government), though Thomson has now ceased to exist in the UK. Brands like Alba, Bush and Murphy are now the preserve of retailers and mail order catalogues who basically just use the name for their own-branded products.

And talking of Ferguson, here’s a selection of Ferguson TV’s and radio’s from the mid 1950s. Ferguson were taken over by the Thorn-EMI empire, which then sold the brand to Thomson (100% owned by the French government), though Thomson has now ceased to exist in the UK. Brands like Alba, Bush and Murphy are now the preserve of retailers and mail order catalogues who basically just use the name for their own-branded products. There were many more brands of television prior to the 1980s, most of which have long since disappeared altogether or absorbed into multinational companies. Here is a picture of the innards of an Ekco television of the mid 1950s.

There were many more brands of television prior to the 1980s, most of which have long since disappeared altogether or absorbed into multinational companies. Here is a picture of the innards of an Ekco television of the mid 1950s. Moving forward ten years to 1965, and the introduction of one of the first ‘affordable’ video tape recording machines – the Philips EL3400. It was bulky and used an exposed reel of tape, plus it only recorded in black and white despite colour transmissions being available not long afterwards. It also had no tuner or timer facility, so it was only useful with (sometimes) expensive external ancillary equipment such as a separate television tuner or video camera. However, two years before the EL3400 there was a British recorder advertised for sale called the Telcan that was possibly the world’s first domestic video recorder. It could record approximately 20 minutes of 405 line video and audio onto audio tape; a remarkable feat for relatively primitive technology but was a commercial failure presumably due to the short length of its recordings. Only two examples of the Telcan are known to exist nowadays.

Moving forward ten years to 1965, and the introduction of one of the first ‘affordable’ video tape recording machines – the Philips EL3400. It was bulky and used an exposed reel of tape, plus it only recorded in black and white despite colour transmissions being available not long afterwards. It also had no tuner or timer facility, so it was only useful with (sometimes) expensive external ancillary equipment such as a separate television tuner or video camera. However, two years before the EL3400 there was a British recorder advertised for sale called the Telcan that was possibly the world’s first domestic video recorder. It could record approximately 20 minutes of 405 line video and audio onto audio tape; a remarkable feat for relatively primitive technology but was a commercial failure presumably due to the short length of its recordings. Only two examples of the Telcan are known to exist nowadays. Compared to the Telcan, the EL3400 was a greater success and certainly had its uses, as a group of dancers watch themselves perform on a large video projection screen. The EL3400 did not come cheap because it used a helical scan recording technique also used by professional recorders like the Ampex Quadraplex (the world’s first broadcast quality video recorder), so it was typically found only in large education establishments or used for industrial applications. Also Japanese companies such as Shibaden and Sony were starting to make their presence felt at this time with recorders like the CV-2000 format reel to reel machines which were soon followed by the U-Matic video cassette that proved popular in the industrial and commercial markets.

Compared to the Telcan, the EL3400 was a greater success and certainly had its uses, as a group of dancers watch themselves perform on a large video projection screen. The EL3400 did not come cheap because it used a helical scan recording technique also used by professional recorders like the Ampex Quadraplex (the world’s first broadcast quality video recorder), so it was typically found only in large education establishments or used for industrial applications. Also Japanese companies such as Shibaden and Sony were starting to make their presence felt at this time with recorders like the CV-2000 format reel to reel machines which were soon followed by the U-Matic video cassette that proved popular in the industrial and commercial markets. The common face of television in the mid to late 1960s – black and white, dual standard (though lots of single-standard 405 line VHF-only televisions remained in use for many years) with separate controls for 405-line VHF and 625-line UHF transmissions. This was required since from 1964 the new BBC2 service was only available on UHF.

The common face of television in the mid to late 1960s – black and white, dual standard (though lots of single-standard 405 line VHF-only televisions remained in use for many years) with separate controls for 405-line VHF and 625-line UHF transmissions. This was required since from 1964 the new BBC2 service was only available on UHF. 1967 saw the arrival of the first mass produced colour TV’s for the UK market, though their high price and initial lack of colour programming (BBC2 only until 1969, few transmitters provided a colour signal and not all programmes were in colour) ensured slow sales to begin with. The picture shows an HMV Colourmaster which was typical of the sets produced in the late 1960s. Find out more about early colour television on the Colour Television page.

1967 saw the arrival of the first mass produced colour TV’s for the UK market, though their high price and initial lack of colour programming (BBC2 only until 1969, few transmitters provided a colour signal and not all programmes were in colour) ensured slow sales to begin with. The picture shows an HMV Colourmaster which was typical of the sets produced in the late 1960s. Find out more about early colour television on the Colour Television page. Fast forward to 1972 – though a few lucky buyers may have had access to one in 1971 – and the launch of the first ‘proper’ ‘home’ video recorder with an integrated tuner and timer, the Philips N1500. This close-up view (disregard the Sony machine just visible) shows the sloping front panel with (from left to right) a recording level meter, tape transport controls, and the 1 day, 1 event ‘egg timer’ clock. Each large Philips VCR cassette could record up to 30 or 60 (later 80) minutes; the six channel selector buttons are visible above the transport controls. The only thing to put off a potential purchaser – apart from the relatively short running time – was the steep price tag. However the N1500 was not generally available until the end of 1973; earlier it was only sold to schools and corporate customers, and these customers remained the main purchasers of such an expensive device. The less than 90 minutes maximum recording time would have limited its appeal to wealthy people who weren’t interested in recording long movies, therefore it tended to be only specialist shops and upmarket department stores that stocked the recorder.

Fast forward to 1972 – though a few lucky buyers may have had access to one in 1971 – and the launch of the first ‘proper’ ‘home’ video recorder with an integrated tuner and timer, the Philips N1500. This close-up view (disregard the Sony machine just visible) shows the sloping front panel with (from left to right) a recording level meter, tape transport controls, and the 1 day, 1 event ‘egg timer’ clock. Each large Philips VCR cassette could record up to 30 or 60 (later 80) minutes; the six channel selector buttons are visible above the transport controls. The only thing to put off a potential purchaser – apart from the relatively short running time – was the steep price tag. However the N1500 was not generally available until the end of 1973; earlier it was only sold to schools and corporate customers, and these customers remained the main purchasers of such an expensive device. The less than 90 minutes maximum recording time would have limited its appeal to wealthy people who weren’t interested in recording long movies, therefore it tended to be only specialist shops and upmarket department stores that stocked the recorder.

CEEFAX had been demonstrated by the BBC to the public as early as a news report on 23 October 1972, but IBA engineers had been independently working on their own ORACLE system therefore it took two years for the two incompatible systems to be reworked into a single standard known as teletext and for broadcasts to commence, with the acronyms CEEFAX and ORACLE being used as the two brand names for the BBC and IBA (ITV) services using the same teletext standard. The falling price of digital electronics made teletext much more affordable during the 1980s and proved to be popular in the UK, remaining in use until it was made obsolete by the analogue TV transmission switch off.

CEEFAX had been demonstrated by the BBC to the public as early as a news report on 23 October 1972, but IBA engineers had been independently working on their own ORACLE system therefore it took two years for the two incompatible systems to be reworked into a single standard known as teletext and for broadcasts to commence, with the acronyms CEEFAX and ORACLE being used as the two brand names for the BBC and IBA (ITV) services using the same teletext standard. The falling price of digital electronics made teletext much more affordable during the 1980s and proved to be popular in the UK, remaining in use until it was made obsolete by the analogue TV transmission switch off.

Before the video cassette recorder (VCR) became popular during the 1980s, it was necessary to explain to potential customers exactly what a VCR was and what it could actually do, and those potential customers may not be mechanically-minded either, so the best person to explain what a VCR did in layman’s terms is someone who is recognisably an expert in television but who isn’t necessarily an expert in things mechanical, namely someone like the writer and presenter Denis Norden, therefore Philips were extremely lucky to be able to have Norden present their promotional video demonstrating the benefits of their brand new N1700 VCR. It’s interesting that Philips chose to describe their VCR as simply a “Time Machine” as opposed to a “Television Time Machine” which would have been a much more precise description of what it could do if perhaps a less eye-catching expression.

Before the video cassette recorder (VCR) became popular during the 1980s, it was necessary to explain to potential customers exactly what a VCR was and what it could actually do, and those potential customers may not be mechanically-minded either, so the best person to explain what a VCR did in layman’s terms is someone who is recognisably an expert in television but who isn’t necessarily an expert in things mechanical, namely someone like the writer and presenter Denis Norden, therefore Philips were extremely lucky to be able to have Norden present their promotional video demonstrating the benefits of their brand new N1700 VCR. It’s interesting that Philips chose to describe their VCR as simply a “Time Machine” as opposed to a “Television Time Machine” which would have been a much more precise description of what it could do if perhaps a less eye-catching expression. The N1700 recorded television broadcasts onto the same size cassette tapes as the N1500, with up to 2 hours of record and play time initially available (Long Play = LP) compared to the 1 hour duration offered by the earlier N1500 series machines (including the N1502 which looked very similar to the N1700); this was achieved by slowing the tape speed down and using improved electronics, therefore recordings were incompatible between VCR-LP and the earlier VCR machines. Even longer tapes were later introduced, enabling 3 hours of recording time on VCR-LP recorders in order to compete with the new VHS and Betamax recorders offered by Japanese manufacturers that were launched in the UK during 1978. (Betamax and VHS had already launched in Japanese/US NTSC markets; 1975 for Betamax and 1976 for VHS respectively, so Philips knew that competition for their product was soon to appear in Europe.)

The N1700 recorded television broadcasts onto the same size cassette tapes as the N1500, with up to 2 hours of record and play time initially available (Long Play = LP) compared to the 1 hour duration offered by the earlier N1500 series machines (including the N1502 which looked very similar to the N1700); this was achieved by slowing the tape speed down and using improved electronics, therefore recordings were incompatible between VCR-LP and the earlier VCR machines. Even longer tapes were later introduced, enabling 3 hours of recording time on VCR-LP recorders in order to compete with the new VHS and Betamax recorders offered by Japanese manufacturers that were launched in the UK during 1978. (Betamax and VHS had already launched in Japanese/US NTSC markets; 1975 for Betamax and 1976 for VHS respectively, so Philips knew that competition for their product was soon to appear in Europe.)

Just like the earlier N1500/N1502 models, the N1700 VCR recorded television broadcasts onto removable cassette tapes, therefore you had to have inserted a tape into the machine in the first place and ensured that there was enough free space on the tape for a new recording, if necessary rewinding the tape to a suitable point (or the beginning) as shown here, but anyone already familiar with audio cassette recording as most people were at that point during the 1970s would instinctively understand such concepts even if people under the age of 25 nowadays would be even more clueless about VCR’s as the average person would have been in the 1970s. The N1700 did the job it was designed to do on a basic level, but it had no remote control and no picture search facility so you had to make use of a mechanical tape counter and/or the tape compartment window to work out exactly how much tape was left for recording/playback.

Just like the earlier N1500/N1502 models, the N1700 VCR recorded television broadcasts onto removable cassette tapes, therefore you had to have inserted a tape into the machine in the first place and ensured that there was enough free space on the tape for a new recording, if necessary rewinding the tape to a suitable point (or the beginning) as shown here, but anyone already familiar with audio cassette recording as most people were at that point during the 1970s would instinctively understand such concepts even if people under the age of 25 nowadays would be even more clueless about VCR’s as the average person would have been in the 1970s. The N1700 did the job it was designed to do on a basic level, but it had no remote control and no picture search facility so you had to make use of a mechanical tape counter and/or the tape compartment window to work out exactly how much tape was left for recording/playback. The N1700 did have a basic digital timer capable of recording one programme that had a start time at some point during the next three days, which at least was an improvement over the first Philips VCR N1500 that could only manage a recording start time during the next 24 hours (and was a mechanical timer similar to that used on an old cooker); the N1700 timer was set using a sliding control which was moved one step at a time from left to right, setting the day, start time, and programme duration in that order. Simple and relatively foolproof if not the last word in sophistication, but anything more complex would have made the N1700 too expensive when Philips was trying to keep the overall product cost down.

The N1700 did have a basic digital timer capable of recording one programme that had a start time at some point during the next three days, which at least was an improvement over the first Philips VCR N1500 that could only manage a recording start time during the next 24 hours (and was a mechanical timer similar to that used on an old cooker); the N1700 timer was set using a sliding control which was moved one step at a time from left to right, setting the day, start time, and programme duration in that order. Simple and relatively foolproof if not the last word in sophistication, but anything more complex would have made the N1700 too expensive when Philips was trying to keep the overall product cost down. If you were really wealthy in the 1970s, you could not only afford a VCR but also have the disposable income to buy an optional camera to plug in the back of it, meaning that you could record home movies on your VCR as long as the lead between camera and VCR was long enough to reach where you wanted to record; fine for recording children playing in the living room or perhaps in the garden from the patio but useless for many other parts of the house or outside. Also the cheap cameras only recorded in black and white, therefore colour recording required additional expense as well as good lighting because the camera tubes weren’t very sensitive to light, so that candlelit dinner party recording may turn out to be a complete washout unless very bright lights were used.

If you were really wealthy in the 1970s, you could not only afford a VCR but also have the disposable income to buy an optional camera to plug in the back of it, meaning that you could record home movies on your VCR as long as the lead between camera and VCR was long enough to reach where you wanted to record; fine for recording children playing in the living room or perhaps in the garden from the patio but useless for many other parts of the house or outside. Also the cheap cameras only recorded in black and white, therefore colour recording required additional expense as well as good lighting because the camera tubes weren’t very sensitive to light, so that candlelit dinner party recording may turn out to be a complete washout unless very bright lights were used.

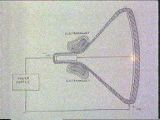

Ever wondered how everyday home appliances such as a fridge, fax machine, or central heating operated? Even if you hadn’t, The Secret Life of Machines series set out to explain simply and clearly how these (and more) items perform their functions. Presented by Tim Hunkin (right) and Rex Garrod, three series of programmes were produced for Channel 4 in 1988, 1991 and 1993 (the third series was entitled The Secret Life of the Office); all pictures shown here are taken from The Secret Life of the Television Set which was the last programme in the first series. Other programmes have since been produced that have names prefixed with “The Secret Life of…” (e.g. The Secret Life of the Zoo), but they are unrelated to The Secret Life of Machines/The Secret Life of the Office.

Ever wondered how everyday home appliances such as a fridge, fax machine, or central heating operated? Even if you hadn’t, The Secret Life of Machines series set out to explain simply and clearly how these (and more) items perform their functions. Presented by Tim Hunkin (right) and Rex Garrod, three series of programmes were produced for Channel 4 in 1988, 1991 and 1993 (the third series was entitled The Secret Life of the Office); all pictures shown here are taken from The Secret Life of the Television Set which was the last programme in the first series. Other programmes have since been produced that have names prefixed with “The Secret Life of…” (e.g. The Secret Life of the Zoo), but they are unrelated to The Secret Life of Machines/The Secret Life of the Office. A special feature is the use of (often humourous) cartoons that are used to illustrate ‘moments in history’ which are relevant to the appliance under discussion. This picture is taken from a cartoon used to show the moment when it was discovered that selenium can cause an electrical voltage to change dependent on the amount of light shining on it.

A special feature is the use of (often humourous) cartoons that are used to illustrate ‘moments in history’ which are relevant to the appliance under discussion. This picture is taken from a cartoon used to show the moment when it was discovered that selenium can cause an electrical voltage to change dependent on the amount of light shining on it. Tim Hunkin (the main presenter and architect of the series) may look exactly like the stereotypical image of “the professor”, but contrary to this he presents technology in a very straightforward and easy to understand manner and manages to do so in a way that can keep the interest of both novices and experts alike. His secret is possibly that if you’re not afraid of technology and you understand how an item works you can “deconstruct” an item into its various simpler components, and also avoiding unneccesary complexity when explaining how something operates.